Google Search Console validation reports"Validation reports in Google Search Console confirm whether previously identified issues have been fixed. These reports help you ensure that corrections are implemented successfully and maintain a healthy, well-optimized website."

Google Search Console validation status"Validation status in Google Search Console shows whether fixed issues have been successfully validated. Best SEO Sydney Agency. By confirming these changes, you ensure that your site remains optimized and fully compliant with Googles guidelines."

Google Search Console video indexing"The video indexing feature in Google Search Console allows you to see how well your video content is indexed. Search Engine Optimisation . By reviewing video indexing data, you can optimize multimedia assets to improve their search visibility."

Google Tag Manager built-in variables"Built-in variables in Google Tag Manager are predefined data points that you can use out-of-the-box, such as page URLs, click text, or referrers. Best Local SEO Services. Using these built-in variables simplifies tag configuration and speeds up implementation."

Google Tag Manager click tracking"Click tracking in Google Tag Manager involves setting up triggers that fire tags when users click on certain elements, like buttons or links.

Google Tag Manager container"A Google Tag Manager container is the code snippet that you place on your website to deploy various tags. Once installed, it allows you to manage all tracking codes and scripts from a central dashboard, reducing dependency on developers."

Google Tag Manager custom event tracking"Custom event tracking in Google Tag Manager enables you to capture unique user actions, such as specific button clicks or video interactions. Best SEO Audit Sydney. By creating custom events, you gain detailed insights into user engagement and can fine-tune your sites performance."

Google Tag Manager custom HTML tags"Custom HTML tags in Google Tag Manager allow you to add custom scripts and code snippets to your site without editing its core files. These tags provide flexibility for advanced tracking scenarios, such as tracking third-party integrations."

Google Tag Manager data layers"The data layer in Google Tag Manager is a structured way to pass information from your website to GTM. It provides a consistent source of data for tags and triggers, simplifying the process of setting up tracking and improving data accuracy."

Google Tag Manager debugging"Debugging in Google Tag Manager involves using built-in tools like preview mode and the browser console to verify that tags fire as intended.

Google Tag Manager eCommerce tracking"ECommerce tracking in Google Tag Manager involves setting up tags and triggers that capture purchase data, product impressions, and checkout behavior. This data feeds into your analytics platform, helping you understand and optimize your online sales funnel."

Google Tag Manager event listeners"Event listeners in Google Tag Manager detect specific user interactions, such as clicks or form submissions. By setting up event listeners, you can track valuable engagement data without manually adding tracking code to your site."

comprehensive SEO Packages Sydney services.Google Tag Manager event tracking"Event tracking through Google Tag Manager lets you monitor user interactions without modifying your sites code. By creating tags, triggers, and variables in GTM, you can track clicks, form submissions, and other events directly in your analytics platform."

Google Tag Manager form tracking"Form tracking in Google Tag Manager lets you monitor when users submit forms on your website. range of SEO Services and Australia . By setting up triggers and tags, you can measure form completions, analyze user behavior, and optimize the form-filling experience."

Google Tag Manager lookup tables"Lookup tables in Google Tag Manager store key-value pairs that help you assign variables based on specific conditions. By using lookup tables, you can streamline complex tag configurations and improve tracking efficiency."

Google Tag Manager multiple containersUsing multiple containers in Google Tag Manager allows you to manage tracking codes across different properties or regions. This approach helps maintain organized workflows and ensures that tags remain accurate and easy to maintain.

Google Tag Manager regex matching"Regex matching in Google Tag Manager allows you to create flexible triggers based on complex patterns. By using regex, you can implement advanced tracking scenarios, such as matching multiple URLs or identifying specific user actions."

Google Tag Manager scroll tracking"Scroll tracking in Google Tag Manager lets you measure how far down a page users scroll. By setting up scroll triggers and tags, you gain insights into content engagement and can optimize page layouts to keep users engaged longer."

Google Tag Manager setup"Setting up Google Tag Manager involves creating a container for your website, adding the GTM code snippet, and configuring tags and triggers within the platform. This setup simplifies tracking code management and enables quick updates without modifying site code."

Google Tag Manager tag sequencing"Tag sequencing in Google Tag Manager controls the order in which tags fire. By setting up tag sequencing, you can ensure that certain tags fire only after prerequisites are met, improving data accuracy and maintaining reliable tracking workflows."

Google Tag Manager tag templates"Tag templates in Google Tag Manager simplify the process of creating and deploying tags. These pre-configured templates for popular platforms like Google Analytics, Google Ads, and Facebook make it easy to add tracking without coding expertise."

| Semantics | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||

| Semantics of programming languages |

||||||||

|

||||||||

The Semantic Web, sometimes known as Web 3.0 (not to be confused with Web3), is an extension of the World Wide Web through standards[1] set by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). The goal of the Semantic Web is to make Internet data machine-readable.

To enable the encoding of semantics with the data, technologies such as Resource Description Framework (RDF)[2] and Web Ontology Language (OWL)[3] are used. These technologies are used to formally represent metadata. For example, ontology can describe concepts, relationships between entities, and categories of things. These embedded semantics offer significant advantages such as reasoning over data and operating with heterogeneous data sources.[4] These standards promote common data formats and exchange protocols on the Web, fundamentally the RDF. According to the W3C, "The Semantic Web provides a common framework that allows data to be shared and reused across application, enterprise, and community boundaries."[5] The Semantic Web is therefore regarded as an integrator across different content and information applications and systems.

The term was coined by Tim Berners-Lee for a web of data (or data web)[6] that can be processed by machines[7]—that is, one in which much of the meaning is machine-readable. While its critics have questioned its feasibility, proponents argue that applications in library and information science, industry, biology and human sciences research have already proven the validity of the original concept.[8]

Berners-Lee originally expressed his vision of the Semantic Web in 1999 as follows:

I have a dream for the Web [in which computers] become capable of analyzing all the data on the Web – the content, links, and transactions between people and computers. A "Semantic Web", which makes this possible, has yet to emerge, but when it does, the day-to-day mechanisms of trade, bureaucracy and our daily lives will be handled by machines talking to machines. The "intelligent agents" people have touted for ages will finally materialize.[9]

The 2001 Scientific American article by Berners-Lee, Hendler, and Lassila described an expected evolution of the existing Web to a Semantic Web.[10] In 2006, Berners-Lee and colleagues stated that: "This simple idea…remains largely unrealized".[11] In 2013, more than four million Web domains (out of roughly 250 million total) contained Semantic Web markup.[12]

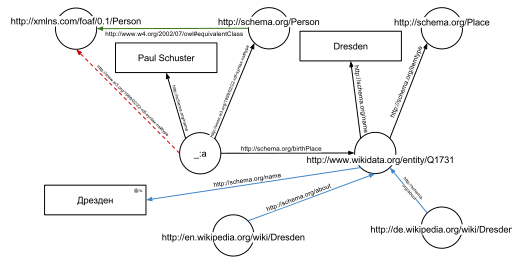

In the following example, the text "Paul Schuster was born in Dresden" on a website will be annotated, connecting a person with their place of birth. The following HTML fragment shows how a small graph is being described, in RDFa-syntax using a schema.org vocabulary and a Wikidata ID:

<div vocab="https://schema.org/" typeof="Person">

<span property="name">Paul Schuster</span> was born in

<span property="birthPlace" typeof="Place" href="https://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q1731">

<span property="name">Dresden</span>.

</span>

</div>

The example defines the following five triples (shown in Turtle syntax). Each triple represents one edge in the resulting graph: the first element of the triple (the subject) is the name of the node where the edge starts, the second element (the predicate) the type of the edge, and the last and third element (the object) either the name of the node where the edge ends or a literal value (e.g. a text, a number, etc.).

_:a <https://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#type> <https://schema.org/Person> .

_:a <https://schema.org/name> "Paul Schuster" .

_:a <https://schema.org/birthPlace> <https://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q1731> .

<https://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q1731> <https://schema.org/itemtype> <https://schema.org/Place> .

<https://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q1731> <https://schema.org/name> "Dresden" .

The triples result in the graph shown in the given figure.

One of the advantages of using Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs) is that they can be dereferenced using the HTTP protocol. According to the so-called Linked Open Data principles, such a dereferenced URI should result in a document that offers further data about the given URI. In this example, all URIs, both for edges and nodes (e.g. http://schema.org/Person, http://schema.org/birthPlace, http://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q1731) can be dereferenced and will result in further RDF graphs, describing the URI, e.g. that Dresden is a city in Germany, or that a person, in the sense of that URI, can be fictional.

The second graph shows the previous example, but now enriched with a few of the triples from the documents that result from dereferencing https://schema.org/Person (green edge) and https://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q1731 (blue edges).

Additionally to the edges given in the involved documents explicitly, edges can be automatically inferred: the triple

_:a <https://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#type> <http://schema.org/Person> .

from the original RDFa fragment and the triple

<https://schema.org/Person> <http://www.w3.org/2002/07/owl#equivalentClass> <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/Person> .

from the document at https://schema.org/Person (green edge in the figure) allow to infer the following triple, given OWL semantics (red dashed line in the second Figure):

_:a <https://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#type> <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/Person> .

The concept of the semantic network model was formed in the early 1960s by researchers such as the cognitive scientist Allan M. Collins, linguist Ross Quillian and psychologist Elizabeth F. Loftus as a form to represent semantically structured knowledge. When applied in the context of the modern internet, it extends the network of hyperlinked human-readable web pages by inserting machine-readable metadata about pages and how they are related to each other. This enables automated agents to access the Web more intelligently and perform more tasks on behalf of users. The term "Semantic Web" was coined by Tim Berners-Lee,[7] the inventor of the World Wide Web and director of the World Wide Web Consortium ("W3C"), which oversees the development of proposed Semantic Web standards. He defines the Semantic Web as "a web of data that can be processed directly and indirectly by machines".

Many of the technologies proposed by the W3C already existed before they were positioned under the W3C umbrella. These are used in various contexts, particularly those dealing with information that encompasses a limited and defined domain, and where sharing data is a common necessity, such as scientific research or data exchange among businesses. In addition, other technologies with similar goals have emerged, such as microformats.

Many files on a typical computer can be loosely divided into either human-readable documents, or machine-readable data. Examples of human-readable document files are mail messages, reports, and brochures. Examples of machine-readable data files are calendars, address books, playlists, and spreadsheets, which are presented to a user using an application program that lets the files be viewed, searched, and combined.

Currently, the World Wide Web is based mainly on documents written in Hypertext Markup Language (HTML), a markup convention that is used for coding a body of text interspersed with multimedia objects such as images and interactive forms. Metadata tags provide a method by which computers can categorize the content of web pages. In the examples below, the field names "keywords", "description" and "author" are assigned values such as "computing", and "cheap widgets for sale" and "John Doe".

<meta name="keywords" content="computing, computer studies, computer" />

<meta name="description" content="Cheap widgets for sale" />

<meta name="author" content="John Doe" />

Because of this metadata tagging and categorization, other computer systems that want to access and share this data can easily identify the relevant values.

With HTML and a tool to render it (perhaps web browser software, perhaps another user agent), one can create and present a page that lists items for sale. The HTML of this catalog page can make simple, document-level assertions such as "this document's title is 'Widget Superstore'", but there is no capability within the HTML itself to assert unambiguously that, for example, item number X586172 is an Acme Gizmo with a retail price of €199, or that it is a consumer product. Rather, HTML can only say that the span of text "X586172" is something that should be positioned near "Acme Gizmo" and "€199", etc. There is no way to say "this is a catalog" or even to establish that "Acme Gizmo" is a kind of title or that "€199" is a price. There is also no way to express that these pieces of information are bound together in describing a discrete item, distinct from other items perhaps listed on the page.

Semantic HTML refers to the traditional HTML practice of markup following intention, rather than specifying layout details directly. For example, the use of <em> denoting "emphasis" rather than <i>, which specifies italics. Layout details are left up to the browser, in combination with Cascading Style Sheets. But this practice falls short of specifying the semantics of objects such as items for sale or prices.

Microformats extend HTML syntax to create machine-readable semantic markup about objects including people, organizations, events and products.[13] Similar initiatives include RDFa, Microdata and Schema.org.

The Semantic Web takes the solution further. It involves publishing in languages specifically designed for data: Resource Description Framework (RDF), Web Ontology Language (OWL), and Extensible Markup Language (XML). HTML describes documents and the links between them. RDF, OWL, and XML, by contrast, can describe arbitrary things such as people, meetings, or airplane parts.

These technologies are combined in order to provide descriptions that supplement or replace the content of Web documents. Thus, content may manifest itself as descriptive data stored in Web-accessible databases,[14] or as markup within documents (particularly, in Extensible HTML (XHTML) interspersed with XML, or, more often, purely in XML, with layout or rendering cues stored separately). The machine-readable descriptions enable content managers to add meaning to the content, i.e., to describe the structure of the knowledge we have about that content. In this way, a machine can process knowledge itself, instead of text, using processes similar to human deductive reasoning and inference, thereby obtaining more meaningful results and helping computers to perform automated information gathering and research.

An example of a tag that would be used in a non-semantic web page:

<item>blog</item>

Encoding similar information in a semantic web page might look like this:

<item rdf:about="https://example.org/semantic-web/">Semantic Web</item>

Tim Berners-Lee calls the resulting network of Linked Data the Giant Global Graph, in contrast to the HTML-based World Wide Web. Berners-Lee posits that if the past was document sharing, the future is data sharing. His answer to the question of "how" provides three points of instruction. One, a URL should point to the data. Two, anyone accessing the URL should get data back. Three, relationships in the data should point to additional URLs with data.

Tags, including hierarchical categories and tags that are collaboratively added and maintained (e.g. with folksonomies) can be considered part of, of potential use to or a step towards the semantic Web vision.[15][16][17]

Unique identifiers, including hierarchical categories and collaboratively added ones, analysis tools and metadata, including tags, can be used to create forms of semantic webs – webs that are to a certain degree semantic.[18] In particular, such has been used for structuring scientific research i.a. by research topics and scientific fields by the projects OpenAlex,[19][20][21] Wikidata and Scholia which are under development and provide APIs, Web-pages, feeds and graphs for various semantic queries.

Tim Berners-Lee has described the Semantic Web as a component of Web 3.0.[22]

People keep asking what Web 3.0 is. I think maybe when you've got an overlay of scalable vector graphics – everything rippling and folding and looking misty – on Web 2.0 and access to a semantic Web integrated across a huge space of data, you'll have access to an unbelievable data resource …

— Tim Berners-Lee, 2006

"Semantic Web" is sometimes used as a synonym for "Web 3.0",[23] though the definition of each term varies.

The next generation of the Web is often termed Web 4.0, but its definition is not clear. According to some sources, it is a Web that involves artificial intelligence,[24] the internet of things, pervasive computing, ubiquitous computing and the Web of Things among other concepts.[25] According to the European Union, Web 4.0 is "the expected fourth generation of the World Wide Web. Using advanced artificial and ambient intelligence, the internet of things, trusted blockchain transactions, virtual worlds and XR capabilities, digital and real objects and environments are fully integrated and communicate with each other, enabling truly intuitive, immersive experiences, seamlessly blending the physical and digital worlds".[26]

Some of the challenges for the Semantic Web include vastness, vagueness, uncertainty, inconsistency, and deceit. Automated reasoning systems will have to deal with all of these issues in order to deliver on the promise of the Semantic Web.

This list of challenges is illustrative rather than exhaustive, and it focuses on the challenges to the "unifying logic" and "proof" layers of the Semantic Web. The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) Incubator Group for Uncertainty Reasoning for the World Wide Web[27] (URW3-XG) final report lumps these problems together under the single heading of "uncertainty".[28] Many of the techniques mentioned here will require extensions to the Web Ontology Language (OWL) for example to annotate conditional probabilities. This is an area of active research.[29]

Standardization for Semantic Web in the context of Web 3.0 is under the care of W3C.[30]

The term "Semantic Web" is often used more specifically to refer to the formats and technologies that enable it.[5] The collection, structuring and recovery of linked data are enabled by technologies that provide a formal description of concepts, terms, and relationships within a given knowledge domain. These technologies are specified as W3C standards and include:

The Semantic Web Stack illustrates the architecture of the Semantic Web. The functions and relationships of the components can be summarized as follows:[31]

Well-established standards:

Not yet fully realized:

The intent is to enhance the usability and usefulness of the Web and its interconnected resources by creating semantic web services, such as:

<meta> tags used in today's Web pages to supply information for Web search engines using web crawlers). This could be machine-understandable information about the human-understandable content of the document (such as the creator, title, description, etc.) or it could be purely metadata representing a set of facts (such as resources and services elsewhere on the site). Note that anything that can be identified with a Uniform Resource Identifier (URI) can be described, so the semantic web can reason about animals, people, places, ideas, etc. There are four semantic annotation formats that can be used in HTML documents; Microformat, RDFa, Microdata and JSON-LD.[35] Semantic markup is often generated automatically, rather than manually.

Such services could be useful to public search engines, or could be used for knowledge management within an organization. Business applications include:

In a corporation, there is a closed group of users and the management is able to enforce company guidelines like the adoption of specific ontologies and use of semantic annotation. Compared to the public Semantic Web there are lesser requirements on scalability and the information circulating within a company can be more trusted in general; privacy is less of an issue outside of handling of customer data.

Critics question the basic feasibility of a complete or even partial fulfillment of the Semantic Web, pointing out both difficulties in setting it up and a lack of general-purpose usefulness that prevents the required effort from being invested. In a 2003 paper, Marshall and Shipman point out the cognitive overhead inherent in formalizing knowledge, compared to the authoring of traditional web hypertext:[46]

While learning the basics of HTML is relatively straightforward, learning a knowledge representation language or tool requires the author to learn about the representation's methods of abstraction and their effect on reasoning. For example, understanding the class-instance relationship, or the superclass-subclass relationship, is more than understanding that one concept is a "type of" another concept. [...] These abstractions are taught to computer scientists generally and knowledge engineers specifically but do not match the similar natural language meaning of being a "type of" something. Effective use of such a formal representation requires the author to become a skilled knowledge engineer in addition to any other skills required by the domain. [...] Once one has learned a formal representation language, it is still often much more effort to express ideas in that representation than in a less formal representation [...]. Indeed, this is a form of programming based on the declaration of semantic data and requires an understanding of how reasoning algorithms will interpret the authored structures.

According to Marshall and Shipman, the tacit and changing nature of much knowledge adds to the knowledge engineering problem, and limits the Semantic Web's applicability to specific domains. A further issue that they point out are domain- or organization-specific ways to express knowledge, which must be solved through community agreement rather than only technical means.[46] As it turns out, specialized communities and organizations for intra-company projects have tended to adopt semantic web technologies greater than peripheral and less-specialized communities.[47] The practical constraints toward adoption have appeared less challenging where domain and scope is more limited than that of the general public and the World-Wide Web.[47]

Finally, Marshall and Shipman see pragmatic problems in the idea of (Knowledge Navigator-style) intelligent agents working in the largely manually curated Semantic Web:[46]

In situations in which user needs are known and distributed information resources are well described, this approach can be highly effective; in situations that are not foreseen and that bring together an unanticipated array of information resources, the Google approach is more robust. Furthermore, the Semantic Web relies on inference chains that are more brittle; a missing element of the chain results in a failure to perform the desired action, while the human can supply missing pieces in a more Google-like approach. [...] cost-benefit tradeoffs can work in favor of specially-created Semantic Web metadata directed at weaving together sensible well-structured domain-specific information resources; close attention to user/customer needs will drive these federations if they are to be successful.

Cory Doctorow's critique ("metacrap")[48] is from the perspective of human behavior and personal preferences. For example, people may include spurious metadata into Web pages in an attempt to mislead Semantic Web engines that naively assume the metadata's veracity. This phenomenon was well known with metatags that fooled the Altavista ranking algorithm into elevating the ranking of certain Web pages: the Google indexing engine specifically looks for such attempts at manipulation. Peter Gärdenfors and Timo Honkela point out that logic-based semantic web technologies cover only a fraction of the relevant phenomena related to semantics.[49][50]

Enthusiasm about the semantic web could be tempered by concerns regarding censorship and privacy. For instance, text-analyzing techniques can now be easily bypassed by using other words, metaphors for instance, or by using images in place of words. An advanced implementation of the semantic web would make it much easier for governments to control the viewing and creation of online information, as this information would be much easier for an automated content-blocking machine to understand. In addition, the issue has also been raised that, with the use of FOAF files and geolocation meta-data, there would be very little anonymity associated with the authorship of articles on things such as a personal blog. Some of these concerns were addressed in the "Policy Aware Web" project[51] and is an active research and development topic.

Another criticism of the semantic web is that it would be much more time-consuming to create and publish content because there would need to be two formats for one piece of data: one for human viewing and one for machines. However, many web applications in development are addressing this issue by creating a machine-readable format upon the publishing of data or the request of a machine for such data. The development of microformats has been one reaction to this kind of criticism. Another argument in defense of the feasibility of semantic web is the likely falling price of human intelligence tasks in digital labor markets, such as Amazon's Mechanical Turk.[citation needed]

Specifications such as eRDF and RDFa allow arbitrary RDF data to be embedded in HTML pages. The GRDDL (Gleaning Resource Descriptions from Dialects of Language) mechanism allows existing material (including microformats) to be automatically interpreted as RDF, so publishers only need to use a single format, such as HTML.

The first research group explicitly focusing on the Corporate Semantic Web was the ACACIA team at INRIA-Sophia-Antipolis, founded in 2002. Results of their work include the RDF(S) based Corese[52] search engine, and the application of semantic web technology in the realm of distributed artificial intelligence for knowledge management (e.g. ontologies and multi-agent systems for corporate semantic Web) [53] and E-learning.[54]

Since 2008, the Corporate Semantic Web research group, located at the Free University of Berlin, focuses on building blocks: Corporate Semantic Search, Corporate Semantic Collaboration, and Corporate Ontology Engineering.[55]

Ontology engineering research includes the question of how to involve non-expert users in creating ontologies and semantically annotated content[56] and for extracting explicit knowledge from the interaction of users within enterprises.

Tim O'Reilly, who coined the term Web 2.0, proposed a long-term vision of the Semantic Web as a web of data, where sophisticated applications are navigating and manipulating it.[57] The data web transforms the World Wide Web from a distributed file system into a distributed database.[58]

cite journal: Cite journal requires |journal= (help)cite book: |work= ignored (help)

|

|

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (December 2014)

|

Web indexing, or Internet indexing, comprises methods for indexing the contents of a website or of the Internet as a whole. Individual websites or intranets may use a back-of-the-book index, while search engines usually use keywords and metadata to provide a more useful vocabulary for Internet or onsite searching. With the increase in the number of periodicals that have articles online, web indexing is also becoming important for periodical websites.[1]

Back-of-the-book-style web indexes may be called "web site A-Z indexes".[2] The implication with "A-Z" is that there is an alphabetical browse view or interface. This interface differs from that of a browse through layers of hierarchical categories (also known as a taxonomy) which are not necessarily alphabetical, but are also found on some web sites. Although an A-Z index could be used to index multiple sites, rather than the multiple pages of a single site, this is unusual.

Metadata web indexing involves assigning keywords, description or phrases to web pages or web sites within a metadata tag (or "meta-tag") field, so that the web page or web site can be retrieved with a list. This method is commonly used by search engine indexing.[3]

|

|

Google Search on desktop

|

|

|

Type of site

|

Web search engine |

|---|---|

| Available in | 149 languages |

| Owner | |

| Revenue | Google Ads |

| URL | google |

| IPv6 support | Yes[1] |

| Commercial | Yes |

| Registration | Optional |

| Launched |

|

| Current status | Online |

| Written in | |

Google Search (also known simply as Google or Google.com) is a search engine operated by Google. It allows users to search for information on the Web by entering keywords or phrases. Google Search uses algorithms to analyze and rank websites based on their relevance to the search query. It is the most popular search engine worldwide.

Google Search is the most-visited website in the world. As of 2020, Google Search has a 92% share of the global search engine market.[3] Approximately 26.75% of Google's monthly global traffic comes from the United States, 4.44% from India, 4.4% from Brazil, 3.92% from the United Kingdom and 3.84% from Japan according to data provided by Similarweb.[4]

The order of search results returned by Google is based, in part, on a priority rank system called "PageRank". Google Search also provides many different options for customized searches, using symbols to include, exclude, specify or require certain search behavior, and offers specialized interactive experiences, such as flight status and package tracking, weather forecasts, currency, unit, and time conversions, word definitions, and more.

The main purpose of Google Search is to search for text in publicly accessible documents offered by web servers, as opposed to other data, such as images or data contained in databases. It was originally developed in 1996 by Larry Page, Sergey Brin, and Scott Hassan.[5][6][7] The search engine would also be set up in the garage of Susan Wojcicki's Menlo Park home.[8] In 2011, Google introduced "Google Voice Search" to search for spoken, rather than typed, words.[9] In 2012, Google introduced a semantic search feature named Knowledge Graph.

Analysis of the frequency of search terms may indicate economic, social and health trends.[10] Data about the frequency of use of search terms on Google can be openly inquired via Google Trends and have been shown to correlate with flu outbreaks and unemployment levels, and provide the information faster than traditional reporting methods and surveys. As of mid-2016, Google's search engine has begun to rely on deep neural networks.[11]

In August 2024, a US judge in Virginia ruled that Google's search engine held an illegal monopoly over Internet search.[12][13] The court found that Google maintained its market dominance by paying large amounts to phone-makers and browser-developers to make Google its default search engine.[13]

Google indexes hundreds of terabytes of information from web pages.[14] For websites that are currently down or otherwise not available, Google provides links to cached versions of the site, formed by the search engine's latest indexing of that page.[15] Additionally, Google indexes some file types, being able to show users PDFs, Word documents, Excel spreadsheets, PowerPoint presentations, certain Flash multimedia content, and plain text files.[16] Users can also activate "SafeSearch", a filtering technology aimed at preventing explicit and pornographic content from appearing in search results.[17]

Despite Google search's immense index, sources generally assume that Google is only indexing less than 5% of the total Internet, with the rest belonging to the deep web, inaccessible through its search tools.[14][18][19]

In 2012, Google changed its search indexing tools to demote sites that had been accused of piracy.[20] In October 2016, Gary Illyes, a webmaster trends analyst with Google, announced that the search engine would be making a separate, primary web index dedicated for mobile devices, with a secondary, less up-to-date index for desktop use. The change was a response to the continued growth in mobile usage, and a push for web developers to adopt a mobile-friendly version of their websites.[21][22] In December 2017, Google began rolling out the change, having already done so for multiple websites.[23]

In August 2009, Google invited web developers to test a new search architecture, codenamed "Caffeine", and give their feedback. The new architecture provided no visual differences in the user interface, but added significant speed improvements and a new "under-the-hood" indexing infrastructure. The move was interpreted in some quarters as a response to Microsoft's recent release of an upgraded version of its own search service, renamed Bing, as well as the launch of Wolfram Alpha, a new search engine based on "computational knowledge".[24][25] Google announced completion of "Caffeine" on June 8, 2010, claiming 50% fresher results due to continuous updating of its index.[26]

With "Caffeine", Google moved its back-end indexing system away from MapReduce and onto Bigtable, the company's distributed database platform.[27][28]

In August 2018, Danny Sullivan from Google announced a broad core algorithm update. As per current analysis done by the industry leaders Search Engine Watch and Search Engine Land, the update was to drop down the medical and health-related websites that were not user friendly and were not providing good user experience. This is why the industry experts named it "Medic".[29]

Google reserves very high standards for YMYL (Your Money or Your Life) pages. This is because misinformation can affect users financially, physically, or emotionally. Therefore, the update targeted particularly those YMYL pages that have low-quality content and misinformation. This resulted in the algorithm targeting health and medical-related websites more than others. However, many other websites from other industries were also negatively affected.[30]

By 2012, it handled more than 3.5 billion searches per day.[31] In 2013 the European Commission found that Google Search favored Google's own products, instead of the best result for consumers' needs.[32] In February 2015 Google announced a major change to its mobile search algorithm which would favor mobile friendly over other websites. Nearly 60% of Google searches come from mobile phones. Google says it wants users to have access to premium quality websites. Those websites which lack a mobile-friendly interface would be ranked lower and it is expected that this update will cause a shake-up of ranks. Businesses who fail to update their websites accordingly could see a dip in their regular websites traffic.[33]

Google's rise was largely due to a patented algorithm called PageRank which helps rank web pages that match a given search string.[34] When Google was a Stanford research project, it was nicknamed BackRub because the technology checks backlinks to determine a site's importance. Other keyword-based methods to rank search results, used by many search engines that were once more popular than Google, would check how often the search terms occurred in a page, or how strongly associated the search terms were within each resulting page. The PageRank algorithm instead analyzes human-generated links assuming that web pages linked from many important pages are also important. The algorithm computes a recursive score for pages, based on the weighted sum of other pages linking to them. PageRank is thought to correlate well with human concepts of importance. In addition to PageRank, Google, over the years, has added many other secret criteria for determining the ranking of resulting pages. This is reported to comprise over 250 different indicators,[35][36] the specifics of which are kept secret to avoid difficulties created by scammers and help Google maintain an edge over its competitors globally.

PageRank was influenced by a similar page-ranking and site-scoring algorithm earlier used for RankDex, developed by Robin Li in 1996. Larry Page's patent for PageRank filed in 1998 includes a citation to Li's earlier patent. Li later went on to create the Chinese search engine Baidu in 2000.[37][38]

In a potential hint of Google's future direction of their Search algorithm, Google's then chief executive Eric Schmidt, said in a 2007 interview with the Financial Times: "The goal is to enable Google users to be able to ask the question such as 'What shall I do tomorrow?' and 'What job shall I take?'".[39] Schmidt reaffirmed this during a 2010 interview with The Wall Street Journal: "I actually think most people don't want Google to answer their questions, they want Google to tell them what they should be doing next."[40]

Because Google is the most popular search engine, many webmasters attempt to influence their website's Google rankings. An industry of consultants has arisen to help websites increase their rankings on Google and other search engines. This field, called search engine optimization, attempts to discern patterns in search engine listings, and then develop a methodology for improving rankings to draw more searchers to their clients' sites. Search engine optimization encompasses both "on page" factors (like body copy, title elements, H1 heading elements and image alt attribute values) and Off Page Optimization factors (like anchor text and PageRank). The general idea is to affect Google's relevance algorithm by incorporating the keywords being targeted in various places "on page", in particular the title element and the body copy (note: the higher up in the page, presumably the better its keyword prominence and thus the ranking). Too many occurrences of the keyword, however, cause the page to look suspect to Google's spam checking algorithms. Google has published guidelines for website owners who would like to raise their rankings when using legitimate optimization consultants.[41] It has been hypothesized, and, allegedly, is the opinion of the owner of one business about which there have been numerous complaints, that negative publicity, for example, numerous consumer complaints, may serve as well to elevate page rank on Google Search as favorable comments.[42] The particular problem addressed in The New York Times article, which involved DecorMyEyes, was addressed shortly thereafter by an undisclosed fix in the Google algorithm. According to Google, it was not the frequently published consumer complaints about DecorMyEyes which resulted in the high ranking but mentions on news websites of events which affected the firm such as legal actions against it. Google Search Console helps to check for websites that use duplicate or copyright content.[43]

In 2013, Google significantly upgraded its search algorithm with "Hummingbird". Its name was derived from the speed and accuracy of the hummingbird.[44] The change was announced on September 26, 2013, having already been in use for a month.[45] "Hummingbird" places greater emphasis on natural language queries, considering context and meaning over individual keywords.[44] It also looks deeper at content on individual pages of a website, with improved ability to lead users directly to the most appropriate page rather than just a website's homepage.[46] The upgrade marked the most significant change to Google search in years, with more "human" search interactions[47] and a much heavier focus on conversation and meaning.[44] Thus, web developers and writers were encouraged to optimize their sites with natural writing rather than forced keywords, and make effective use of technical web development for on-site navigation.[48]

In 2023, drawing on internal Google documents disclosed as part of the United States v. Google LLC (2020) antitrust case, technology reporters claimed that Google Search was "bloated and overmonetized"[49] and that the "semantic matching" of search queries put advertising profits before quality.[50] Wired withdrew Megan Gray's piece after Google complained about alleged inaccuracies, while the author reiterated that «As stated in court, "A goal of Project Mercury was to increase commercial queries"».[51]

In March 2024, Google announced a significant update to its core search algorithm and spam targeting, which is expected to wipe out 40 percent of all spam results.[52] On March 20th, it was confirmed that the roll out of the spam update was complete.[53]

On September 10, 2024, the European-based EU Court of Justice found that Google held an illegal monopoly with the way the company showed favoritism to its shopping search, and could not avoid paying €2.4 billion.[54] The EU Court of Justice referred to Google's treatment of rival shopping searches as "discriminatory" and in violation of the Digital Markets Act.[54]

At the top of the search page, the approximate result count and the response time two digits behind decimal is noted. Of search results, page titles and URLs, dates, and a preview text snippet for each result appears. Along with web search results, sections with images, news, and videos may appear.[55] The length of the previewed text snipped was experimented with in 2015 and 2017.[56][57]

"Universal search" was launched by Google on May 16, 2007, as an idea that merged the results from different kinds of search types into one. Prior to Universal search, a standard Google search would consist of links only to websites. Universal search, however, incorporates a wide variety of sources, including websites, news, pictures, maps, blogs, videos, and more, all shown on the same search results page.[58][59] Marissa Mayer, then-vice president of search products and user experience, described the goal of Universal search as "we're attempting to break down the walls that traditionally separated our various search properties and integrate the vast amounts of information available into one simple set of search results.[60]

In June 2017, Google expanded its search results to cover available job listings. The data is aggregated from various major job boards and collected by analyzing company homepages. Initially only available in English, the feature aims to simplify finding jobs suitable for each user.[61][62]

In May 2009, Google announced that they would be parsing website microformats to populate search result pages with "Rich snippets". Such snippets include additional details about results, such as displaying reviews for restaurants and social media accounts for individuals.[63]

In May 2016, Google expanded on the "Rich snippets" format to offer "Rich cards", which, similarly to snippets, display more information about results, but shows them at the top of the mobile website in a swipeable carousel-like format.[64] Originally limited to movie and recipe websites in the United States only, the feature expanded to all countries globally in 2017.[65]

The Knowledge Graph is a knowledge base used by Google to enhance its search engine's results with information gathered from a variety of sources.[66] This information is presented to users in a box to the right of search results.[67] Knowledge Graph boxes were added to Google's search engine in May 2012,[66] starting in the United States, with international expansion by the end of the year.[68] The information covered by the Knowledge Graph grew significantly after launch, tripling its original size within seven months,[69] and being able to answer "roughly one-third" of the 100 billion monthly searches Google processed in May 2016.[70] The information is often used as a spoken answer in Google Assistant[71] and Google Home searches.[72] The Knowledge Graph has been criticized for providing answers without source attribution.[70]

A Google Knowledge Panel[73] is a feature integrated into Google search engine result pages, designed to present a structured overview of entities such as individuals, organizations, locations, or objects directly within the search interface. This feature leverages data from Google's Knowledge Graph,[74] a database that organizes and interconnects information about entities, enhancing the retrieval and presentation of relevant content to users.

The content within a Knowledge Panel[75] is derived from various sources, including Wikipedia and other structured databases, ensuring that the information displayed is both accurate and contextually relevant. For instance, querying a well-known public figure may trigger a Knowledge Panel displaying essential details such as biographical information, birthdate, and links to social media profiles or official websites.

The primary objective of the Google Knowledge Panel is to provide users with immediate, factual answers, reducing the need for extensive navigation across multiple web pages.

In May 2017, Google enabled a new "Personal" tab in Google Search, letting users search for content in their Google accounts' various services, including email messages from Gmail and photos from Google Photos.[76][77]

Google Discover, previously known as Google Feed, is a personalized stream of articles, videos, and other news-related content. The feed contains a "mix of cards" which show topics of interest based on users' interactions with Google, or topics they choose to follow directly.[78] Cards include, "links to news stories, YouTube videos, sports scores, recipes, and other content based on what [Google] determined you're most likely to be interested in at that particular moment."[78] Users can also tell Google they're not interested in certain topics to avoid seeing future updates.

Google Discover launched in December 2016[79] and received a major update in July 2017.[80] Another major update was released in September 2018, which renamed the app from Google Feed to Google Discover, updated the design, and adding more features.[81]

Discover can be found on a tab in the Google app and by swiping left on the home screen of certain Android devices. As of 2019, Google will not allow political campaigns worldwide to target their advertisement to people to make them vote.[82]

At the 2023 Google I/O event in May, Google unveiled Search Generative Experience (SGE), an experimental feature in Google Search available through Google Labs which produces AI-generated summaries in response to search prompts.[83] This was part of Google's wider efforts to counter the unprecedented rise of generative AI technology, ushered by OpenAI's launch of ChatGPT, which sent Google executives to a panic due to its potential threat to Google Search.[84] Google added the ability to generate images in October.[85] At I/O in 2024, the feature was upgraded and renamed AI Overviews.[86]

AI Overviews was rolled out to users in the United States in May 2024.[86] The feature faced public criticism in the first weeks of its rollout after errors from the tool went viral online. These included results suggesting users add glue to pizza or eat rocks,[87] or incorrectly claiming Barack Obama is Muslim.[88] Google described these viral errors as "isolated examples", maintaining that most AI Overviews provide accurate information.[87][89] Two weeks after the rollout of AI Overviews, Google made technical changes and scaled back the feature, pausing its use for some health-related queries and limiting its reliance on social media posts.[90] Scientific American has criticised the system on environmental grounds, as such a search uses 30 times more energy than a conventional one.[91] It has also been criticized for condensing information from various sources, making it less likely for people to view full articles and websites. When it was announced in May 2024, Danielle Coffey, CEO of the News/Media Alliance was quoted as saying "This will be catastrophic to our traffic, as marketed by Google to further satisfy user queries, leaving even less incentive to click through so that we can monetize our content."[92]

In August 2024, AI Overviews were rolled out in the UK, India, Japan, Indonesia, Mexico and Brazil, with local language support.[93] On October 28, 2024, AI Overviews was rolled out to 100 more countries, including Australia and New Zealand.[94]

In March 2025, Google introduced an experimental "AI Mode" within its Search platform, enabling users to input complex, multi-part queries and receive comprehensive, AI-generated responses. This feature leverages Google's advanced Gemini 2.0 model, which enhances the system's reasoning capabilities and supports multimodal inputs, including text, images, and voice.

Initially, AI Mode is available to Google One AI Premium subscribers in the United States, who can access it through the Search Labs platform. This phased rollout allows Google to gather user feedback and refine the feature before a broader release.

The introduction of AI Mode reflects Google's ongoing efforts to integrate advanced AI technologies into its services, aiming to provide users with more intuitive and efficient search experiences.[95][96]

In late June 2011, Google introduced a new look to the Google homepage in order to boost the use of the Google+ social tools.[97]

One of the major changes was replacing the classic navigation bar with a black one. Google's digital creative director Chris Wiggins explains: "We're working on a project to bring you a new and improved Google experience, and over the next few months, you'll continue to see more updates to our look and feel."[98] The new navigation bar has been negatively received by a vocal minority.[99]

In November 2013, Google started testing yellow labels for advertisements displayed in search results, to improve user experience. The new labels, highlighted in yellow color, and aligned to the left of each sponsored link help users differentiate between organic and sponsored results.[100]

On December 15, 2016, Google rolled out a new desktop search interface that mimics their modular mobile user interface. The mobile design consists of a tabular design that highlights search features in boxes. and works by imitating the desktop Knowledge Graph real estate, which appears in the right-hand rail of the search engine result page, these featured elements frequently feature Twitter carousels, People Also Search For, and Top Stories (vertical and horizontal design) modules. The Local Pack and Answer Box were two of the original features of the Google SERP that were primarily showcased in this manner, but this new layout creates a previously unseen level of design consistency for Google results.[101]

Google offers a "Google Search" mobile app for Android and iOS devices.[102] The mobile apps exclusively feature Google Discover and a "Collections" feature, in which the user can save for later perusal any type of search result like images, bookmarks or map locations into groups.[103] Android devices were introduced to a preview of the feed, perceived as related to Google Now, in December 2016,[104] while it was made official on both Android and iOS in July 2017.[105][106]

In April 2016, Google updated its Search app on Android to feature "Trends"; search queries gaining popularity appeared in the autocomplete box along with normal query autocompletion.[107] The update received significant backlash, due to encouraging search queries unrelated to users' interests or intentions, prompting the company to issue an update with an opt-out option.[108] In September 2017, the Google Search app on iOS was updated to feature the same functionality.[109]

In December 2017, Google released "Google Go", an app designed to enable use of Google Search on physically smaller and lower-spec devices in multiple languages. A Google blog post about designing "India-first" products and features explains that it is "tailor-made for the millions of people in [India and Indonesia] coming online for the first time".[110]

Google Search consists of a series of localized websites. The largest of those, the google.com site, is the top most-visited website in the world.[111] Some of its features include a definition link for most searches including dictionary words, the number of results you got on your search, links to other searches (e.g. for words that Google believes to be misspelled, it provides a link to the search results using its proposed spelling), the ability to filter results to a date range,[112] and many more.

Google search accepts queries as normal text, as well as individual keywords.[113] It automatically corrects apparent misspellings by default (while offering to use the original spelling as a selectable alternative), and provides the same results regardless of capitalization.[113] For more customized results, one can use a wide variety of operators, including, but not limited to:[114][115]

OR or | – Search for webpages containing one of two similar queries, such as marathon OR raceAND – Search for webpages containing two similar queries, such as marathon AND runner- (minus sign) – Exclude a word or a phrase, so that "apple -tree" searches where word "tree" is not used"" – Force inclusion of a word or a phrase, such as "tallest building"* – Placeholder symbol allowing for any substitute words in the context of the query, such as "largest * in the world".. – Search within a range of numbers, such as "camera $50..$100"site: – Search within a specific website, such as "site:youtube.com"define: – Search for definitions for a word or phrase, such as "define:phrase"stocks: – See the stock price of investments, such as "stocks:googl"related: – Find web pages related to specific URL addresses, such as "related:www.wikipedia.org"cache: – Highlights the search-words within the cached pages, so that "cache:www.google.com xxx" shows cached content with word "xxx" highlighted.( ) – Group operators and searches, such as (marathon OR race) AND shoesfiletype: or ext: – Search for specific file types, such as filetype:gifbefore: – Search for before a specific date, such as spacex before:2020-08-11after: – Search for after a specific date, such as iphone after:2007-06-29@ – Search for a specific word on social media networks, such as "@twitter"Google also offers a Google Advanced Search page with a web interface to access the advanced features without needing to remember the special operators.[116]

Google applies query expansion to submitted search queries, using techniques to deliver results that it considers "smarter" than the query users actually submitted. This technique involves several steps, including:[117]

In 2008, Google started to give users autocompleted search suggestions in a list below the search bar while typing, originally with the approximate result count previewed for each listed search suggestion.[118]

Google's homepage includes a button labeled "I'm Feeling Lucky". This feature originally allowed users to type in their search query, click the button and be taken directly to the first result, bypassing the search results page. Clicking it while leaving the search box empty opens Google's archive of Doodles.[119] With the 2010 announcement of Google Instant, an automatic feature that immediately displays relevant results as users are typing in their query, the "I'm Feeling Lucky" button disappears, requiring that users opt-out of Instant results through search settings to keep using the "I'm Feeling Lucky" functionality.[120] In 2012, "I'm Feeling Lucky" was changed to serve as an advertisement for Google services; users hover their computer mouse over the button, it spins and shows an emotion ("I'm Feeling Puzzled" or "I'm Feeling Trendy", for instance), and, when clicked, takes users to a Google service related to that emotion.[121]

Tom Chavez of "Rapt", a firm helping to determine a website's advertising worth, estimated in 2007 that Google lost $110 million in revenue per year due to use of the button, which bypasses the advertisements found on the search results page.[122]

Besides the main text-based search-engine function of Google search, it also offers multiple quick, interactive features. These include, but are not limited to:[123][124][125]

During Google's developer conference, Google I/O, in May 2013, the company announced that users on Google Chrome and ChromeOS would be able to have the browser initiate an audio-based search by saying "OK Google", with no button presses required. After having the answer presented, users can follow up with additional, contextual questions; an example include initially asking "OK Google, will it be sunny in Santa Cruz this weekend?", hearing a spoken answer, and reply with "how far is it from here?"[126][127] An update to the Chrome browser with voice-search functionality rolled out a week later, though it required a button press on a microphone icon rather than "OK Google" voice activation.[128] Google released a browser extension for the Chrome browser, named with a "beta" tag for unfinished development, shortly thereafter.[129] In May 2014, the company officially added "OK Google" into the browser itself;[130] they removed it in October 2015, citing low usage, though the microphone icon for activation remained available.[131] In May 2016, 20% of search queries on mobile devices were done through voice.[132]

|

|

|

Type of site

|

Video search engine |

|---|---|

| Available in | Multilingual |

| Owner | |

| URL | www |

| Commercial | Yes |

| Registration | Recommended |

| Launched | August 20, 2012 |

In addition to its tool for searching web pages, Google also provides services for searching images, Usenet newsgroups, news websites, videos (Google Videos), searching by locality, maps, and items for sale online. Google Videos allows searching the World Wide Web for video clips.[133] The service evolved from Google Video, Google's discontinued video hosting service that also allowed to search the web for video clips.[133]

In 2012, Google has indexed over 30 trillion web pages, and received 100 billion queries per month.[134] It also caches much of the content that it indexes. Google operates other tools and services including Google News, Google Shopping, Google Maps, Google Custom Search, Google Earth, Google Docs, Picasa (discontinued), Panoramio (discontinued), YouTube, Google Translate, Google Blog Search and Google Desktop Search (discontinued[135]).

There are also products available from Google that are not directly search-related. Gmail, for example, is a webmail application, but still includes search features; Google Browser Sync does not offer any search facilities, although it aims to organize your browsing time.

In 2009, Google claimed that a search query requires altogether about 1 kJ or 0.0003 kW·h,[136] which is enough to raise the temperature of one liter of water by 0.24 °C. According to green search engine Ecosia, the industry standard for search engines is estimated to be about 0.2 grams of CO2 emission per search.[137] Google's 40,000 searches per second translate to 8 kg CO2 per second or over 252 million kilos of CO2 per year.[138]

On certain occasions, the logo on Google's webpage will change to a special version, known as a "Google Doodle". This is a picture, drawing, animation, or interactive game that includes the logo. It is usually done for a special event or day although not all of them are well known.[139] Clicking on the Doodle links to a string of Google search results about the topic. The first was a reference to the Burning Man Festival in 1998,[140][141] and others have been produced for the birthdays of notable people like Albert Einstein, historical events like the interlocking Lego block's 50th anniversary and holidays like Valentine's Day.[142] Some Google Doodles have interactivity beyond a simple search, such as the famous "Google Pac-Man" version that appeared on May 21, 2010.

Google has been criticized for placing long-term cookies on users' machines to store preferences, a tactic which also enables them to track a user's search terms and retain the data for more than a year.[143]

Since 2012, Google Inc. has globally introduced encrypted connections for most of its clients, to bypass governative blockings of the commercial and IT services.[144]

In 2003, The New York Times complained about Google's indexing, claiming that Google's caching of content on its site infringed its copyright for the content.[145] In both Field v. Google and Parker v. Google, the United States District Court of Nevada ruled in favor of Google.[146][147]

A 2019 New York Times article on Google Search showed that images of child sexual abuse had been found on Google and that the company had been reluctant at times to remove them.[148]

Google flags search results with the message "This site may harm your computer" if the site is known to install malicious software in the background or otherwise surreptitiously. For approximately 40 minutes on January 31, 2009, all search results were mistakenly classified as malware and could therefore not be clicked; instead a warning message was displayed and the user was required to enter the requested URL manually. The bug was caused by human error.[149][150][151][152] The URL of "/" (which expands to all URLs) was mistakenly added to the malware patterns file.[150][151]

In 2007, a group of researchers observed a tendency for users to rely exclusively on Google Search for finding information, writing that "With the Google interface the user gets the impression that the search results imply a kind of totality. ... In fact, one only sees a small part of what one could see if one also integrates other research tools."[153]

In 2011, Google Search query results have been shown by Internet activist Eli Pariser to be tailored to users, effectively isolating users in what he defined as a filter bubble. Pariser holds algorithms used in search engines such as Google Search responsible for catering "a personal ecosystem of information".[154] Although contrasting views have mitigated the potential threat of "informational dystopia" and questioned the scientific nature of Pariser's claims,[155] filter bubbles have been mentioned to account for the surprising results of the U.S. presidential election in 2016 alongside fake news and echo chambers, suggesting that Facebook and Google have designed personalized online realities in which "we only see and hear what we like".[156]

In 2012, the US Federal Trade Commission fined Google US$22.5 million for violating their agreement not to violate the privacy of users of Apple's Safari web browser.[157] The FTC was also continuing to investigate if Google's favoring of their own services in their search results violated antitrust regulations.[158]

In a November 2023 disclosure, during the ongoing antitrust trial against Google, an economics professor at the University of Chicago revealed that Google pays Apple 36% of all search advertising revenue generated when users access Google through the Safari browser. This revelation reportedly caused Google's lead attorney to cringe visibly.[citation needed] The revenue generated from Safari users has been kept confidential, but the 36% figure suggests that it is likely in the tens of billions of dollars.

Both Apple and Google have argued that disclosing the specific terms of their search default agreement would harm their competitive positions. However, the court ruled that the information was relevant to the antitrust case and ordered its disclosure. This revelation has raised concerns about the dominance of Google in the search engine market and the potential anticompetitive effects of its agreements with Apple.[159]

Google search engine robots are programmed to use algorithms that understand and predict human behavior. The book, Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code[160] by Ruha Benjamin talks about human bias as a behavior that the Google search engine can recognize. In 2016, some users Google searched "three Black teenagers" and images of criminal mugshots of young African American teenagers came up. Then, the users searched "three White teenagers" and were presented with photos of smiling, happy teenagers. They also searched for "three Asian teenagers", and very revealing photos of Asian girls and women appeared. Benjamin concluded that these results reflect human prejudice and views on different ethnic groups. A group of analysts explained the concept of a racist computer program: "The idea here is that computers, unlike people, can't be racist but we're increasingly learning that they do in fact take after their makers ... Some experts believe that this problem might stem from the hidden biases in the massive piles of data that the algorithms process as they learn to recognize patterns ... reproducing our worst values".[160]

On August 5, 2024, Google lost a lawsuit which started in 2020 in D.C. Circuit Court, with Judge Amit Mehta finding that the company had an illegal monopoly over Internet search.[161] This monopoly was held to be in violation of Section 2 of the Sherman Act.[162] Google has said it will appeal the ruling,[163] though they did propose to loosen search deals with Apple and others requiring them to set Google as the default search engine.[164]

As people talk about "googling" rather than searching, the company has taken some steps to defend its trademark, in an effort to prevent it from becoming a generic trademark.[165][166] This has led to lawsuits, threats of lawsuits, and the use of euphemisms, such as calling Google Search a famous web search engine.[167]

Until May 2013, Google Search had offered a feature to translate search queries into other languages. A Google spokesperson told Search Engine Land that "Removing features is always tough, but we do think very hard about each decision and its implications for our users. Unfortunately, this feature never saw much pick up".[168]

Instant search was announced in September 2010 as a feature that displayed suggested results while the user typed in their search query, initially only in select countries or to registered users.[169] The primary advantage of the new system was its ability to save time, with Marissa Mayer, then-vice president of search products and user experience, proclaiming that the feature would save 2–5 seconds per search, elaborating that "That may not seem like a lot at first, but it adds up. With Google Instant, we estimate that we'll save our users 11 hours with each passing second!"[170] Matt Van Wagner of Search Engine Land wrote that "Personally, I kind of like Google Instant and I think it represents a natural evolution in the way search works", and also praised Google's efforts in public relations, writing that "With just a press conference and a few well-placed interviews, Google has parlayed this relatively minor speed improvement into an attention-grabbing front-page news story".[171] The upgrade also became notable for the company switching Google Search's underlying technology from HTML to AJAX.[172]

Instant Search could be disabled via Google's "preferences" menu for those who didn't want its functionality.[173]

The publication 2600: The Hacker Quarterly compiled a list of words that Google Instant did not show suggested results for, with a Google spokesperson giving the following statement to Mashable:[174]

There are several reasons you may not be seeing search queries for a particular topic. Among other things, we apply a narrow set of removal policies for pornography, violence, and hate speech. It's important to note that removing queries from Autocomplete is a hard problem, and not as simple as blacklisting particular terms and phrases.

In search, we get more than one billion searches each day. Because of this, we take an algorithmic approach to removals, and just like our search algorithms, these are imperfect. We will continue to work to improve our approach to removals in Autocomplete, and are listening carefully to feedback from our users.

Our algorithms look not only at specific words, but compound queries based on those words, and across all languages. So, for example, if there's a bad word in Russian, we may remove a compound word including the transliteration of the Russian word into English. We also look at the search results themselves for given queries. So, for example, if the results for a particular query seem pornographic, our algorithms may remove that query from Autocomplete, even if the query itself wouldn't otherwise violate our policies. This system is neither perfect nor instantaneous, and we will continue to work to make it better.

PC Magazine discussed the inconsistency in how some forms of the same topic are allowed; for instance, "lesbian" was blocked, while "gay" was not, and "cocaine" was blocked, while "crack" and "heroin" were not. The report further stated that seemingly normal words were also blocked due to pornographic innuendos, most notably "scat", likely due to having two completely separate contextual meanings, one for music and one for a sexual practice.[175]

On July 26, 2017, Google removed Instant results, due to a growing number of searches on mobile devices, where interaction with search, as well as screen sizes, differ significantly from a computer.[176][177]

Instant previews[edit]

"Instant previews" allowed previewing screenshots of search results' web pages without having to open them. The feature was introduced in November 2010 to the desktop website and removed in April 2013 citing low usage.[178][179]

Various search engines provide encrypted Web search facilities. In May 2010 Google rolled out SSL-encrypted web search.[180] The encrypted search was accessed at encrypted.google.com[181] However, the web search is encrypted via Transport Layer Security (TLS) by default today, thus every search request should be automatically encrypted if TLS is supported by the web browser.[182] On its support website, Google announced that the address encrypted.google.com would be turned off April 30, 2018, stating that all Google products and most new browsers use HTTPS connections as the reason for the discontinuation.[183]

Google Real-Time Search was a feature of Google Search in which search results also sometimes included real-time information from sources such as Twitter, Facebook, blogs, and news websites.[184] The feature was introduced on December 7, 2009,[185] and went offline on July 2, 2011, after the deal with Twitter expired.[186] Real-Time Search included Facebook status updates beginning on February 24, 2010.[187] A feature similar to Real-Time Search was already available on Microsoft's Bing search engine, which showed results from Twitter and Facebook.[188] The interface for the engine showed a live, descending "river" of posts in the main region (which could be paused or resumed), while a bar chart metric of the frequency of posts containing a certain search term or hashtag was located on the right hand corner of the page above a list of most frequently reposted posts and outgoing links. Hashtag search links were also supported, as were "promoted" tweets hosted by Twitter (located persistently on top of the river) and thumbnails of retweeted image or video links.

In January 2011, geolocation links of posts were made available alongside results in Real-Time Search. In addition, posts containing syndicated or attached shortened links were made searchable by the link: query option. In July 2011, Real-Time Search became inaccessible, with the Real-Time link in the Google sidebar disappearing and a custom 404 error page generated by Google returned at its former URL. Google originally suggested that the interruption was temporary and related to the launch of Google+;[189] they subsequently announced that it was due to the expiry of a commercial arrangement with Twitter to provide access to tweets.[190]

This onscreen Google slide had to do with a "semantic matching" overhaul to its SERP algorithm. When you enter a query, you might expect a search engine to incorporate synonyms into the algorithm as well as text phrase pairings in natural language processing. But this overhaul went further, actually altering queries to generate more commercial results.

Since Dec. 4, 2009, Google has been personalized for everyone. So when I had two friends this spring Google 'BP,' one of them got a set of links that was about investment opportunities in BP. The other one got information about the oil spill

The global village that was once the internet ... digital islands of isolation that are drifting further apart each day ... your experience online grows increasingly personalized

cite news: |last2= has generic name (help)Google Instant only works for searchers in the US or who are logged in to a Google account in selected countries outside the US

cite web: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Search engine optimisation consultants analyze your website and its performance, identify issues, and recommend strategies to improve your search rankings. They provide guidance on keyword selection, on-page optimization, link building, and content strategy to increase visibility and attract more traffic.

A local SEO agency specializes in improving a business's visibility within a specific geographic area. They focus on optimizing local citations, managing Google My Business profiles, and targeting location-based keywords to attract nearby customers.

SEO, or search engine optimisation, means improving your website's structure, content, and overall performance to rank higher in search results. This leads to more organic traffic, increased brand visibility, and better conversion rates, ultimately supporting your business's growth.

Local SEO helps small businesses attract customers from their immediate area, which is crucial for brick-and-mortar stores and service providers. By optimizing local listings, using location-based keywords, and maintaining accurate NAP information, you increase visibility, build trust, and drive more foot traffic.

SEO packages in Australia typically bundle essential optimization services such as keyword research, technical audits, content creation, and link building at a set price. They are designed to simplify the process, provide consistent results, and help businesses of all sizes improve their online visibility.

A digital agency in Sydney can offer a comprehensive approach, combining SEO with other marketing strategies like social media, PPC, and content marketing. By integrating these services, they help you achieve a stronger online presence and better ROI.