Experience outstanding online performance through SEO copywriting Parramatta Our expert team specialises in delivering solutions that improve rankings, drive engagement, and generate valuable leads for consistent business growth in Parramatta

Choose excellence in digital marketing with Professional web developers Parramatta Our proven approaches drive website traffic, enhance customer engagement, and significantly improve conversion rates, supporting long-term business success in Parramatta

Transform your business growth with Parramatta website speed optimisation Our strategies enhance visibility, attract targeted traffic, and maximise conversions for sustained success Partner with us for measurable digital marketing outcomes today

Best SEO Agency Parramatta Australia.Choose excellence in digital marketing with SEO keyword research Parramatta Our proven approaches drive website traffic, enhance customer engagement, and significantly improve conversion rates, supporting long-term business success in Parramatta

Choose excellence in digital marketing with Parramatta web design team Our proven approaches drive website traffic, enhance customer engagement, and significantly improve conversion rates, supporting long-term business success in Parramatta

Transform your business growth with Creative agencies Parramatta Our strategies enhance visibility, attract targeted traffic, and maximise conversions for sustained success Partner with us for measurable digital marketing outcomes today

Effective Web Design Parramatta Sydney.Choose excellence in digital marketing with Parramatta SEO performance Our proven approaches drive website traffic, enhance customer engagement, and significantly improve conversion rates, supporting long-term business success in Parramatta

Maximise your business potential with Parramatta business websites We deliver impactful strategies designed to boost your brand awareness, improve online visibility, and generate a steady flow of qualified leads in Parramatta

Take your digital presence further with SEO website redesign Parramatta We develop custom strategies aimed at increasing your online visibility, improving search engine rankings, and achieving sustainable growth for your Parramatta-based business

Best Local SEO Parramatta.

Transform your business growth with Web design solutions Parramatta Our strategies enhance visibility, attract targeted traffic, and maximise conversions for sustained success Partner with us for measurable digital marketing outcomes today

Take your digital presence further with Search engine ranking Parramatta We develop custom strategies aimed at increasing your online visibility, improving search engine rankings, and achieving sustainable growth for your Parramatta-based business

Choose excellence in digital marketing with Parramatta SEO tools Our proven approaches drive website traffic, enhance customer engagement, and significantly improve conversion rates, supporting long-term business success in Parramatta

range of SEO Packages Parramatta Sydney.Take your digital presence further with Parramatta content marketing We develop custom strategies aimed at increasing your online visibility, improving search engine rankings, and achieving sustainable growth for your Parramatta-based business

Transform your business growth with SEO growth marketing Parramatta Our strategies enhance visibility, attract targeted traffic, and maximise conversions for sustained success Partner with us for measurable digital marketing outcomes today

Transform your business growth with SEO metrics Parramatta Our strategies enhance visibility, attract targeted traffic, and maximise conversions for sustained success Partner with us for measurable digital marketing outcomes today

Take your digital presence further with Website traffic growth Parramatta We develop custom strategies aimed at increasing your online visibility, improving search engine rankings, and achieving sustainable growth for your Parramatta-based business

Take your digital presence further with Parramatta web branding We develop custom strategies aimed at increasing your online visibility, improving search engine rankings, and achieving sustainable growth for your Parramatta-based business

Maximise your business potential with Online business visibility Parramatta We deliver impactful strategies designed to boost your brand awareness, improve online visibility, and generate a steady flow of qualified leads in Parramatta

Choose excellence in digital marketing with Website analytics Parramatta Our proven approaches drive website traffic, enhance customer engagement, and significantly improve conversion rates, supporting long-term business success in Parramatta

Choose excellence in digital marketing with High-converting websites Parramatta Our proven approaches drive website traffic, enhance customer engagement, and significantly improve conversion rates, supporting long-term business success in Parramatta

Transform your business growth with Parramatta logo and web design Our strategies enhance visibility, attract targeted traffic, and maximise conversions for sustained success Partner with us for measurable digital marketing outcomes today

Web design encompasses many different skills and disciplines in the production and maintenance of websites. The different areas of web design include web graphic design; user interface design (UI design); authoring, including standardised code and proprietary software; user experience design (UX design); and search engine optimization. Often many individuals will work in teams covering different aspects of the design process, although some designers will cover them all.[1] The term "web design" is normally used to describe the design process relating to the front-end (client side) design of a website including writing markup. Web design partially overlaps web engineering in the broader scope of web development. Web designers are expected to have an awareness of usability and be up to date with web accessibility guidelines.

Although web design has a fairly recent history, it can be linked to other areas such as graphic design, user experience, and multimedia arts, but is more aptly seen from a technological standpoint. It has become a large part of people's everyday lives. It is hard to imagine the Internet without animated graphics, different styles of typography, backgrounds, videos and music. The web was announced on August 6, 1991; in November 1992, CERN was the first website to go live on the World Wide Web. During this period, websites were structured by using the <table> tag which created numbers on the website. Eventually, web designers were able to find their way around it to create more structures and formats. In early history, the structure of the websites was fragile and hard to contain, so it became very difficult to use them. In November 1993, ALIWEB was the first ever search engine to be created (Archie Like Indexing for the WEB).[2]

In 1989, whilst working at CERN in Switzerland, British scientist Tim Berners-Lee proposed to create a global hypertext project, which later became known as the World Wide Web. From 1991 to 1993 the World Wide Web was born. Text-only HTML pages could be viewed using a simple line-mode web browser.[3] In 1993 Marc Andreessen and Eric Bina, created the Mosaic browser. At the time there were multiple browsers, however the majority of them were Unix-based and naturally text-heavy. There had been no integrated approach to graphic design elements such as images or sounds. The Mosaic browser broke this mould.[4] The W3C was created in October 1994 to "lead the World Wide Web to its full potential by developing common protocols that promote its evolution and ensure its interoperability."[5] This discouraged any one company from monopolizing a proprietary browser and programming language, which could have altered the effect of the World Wide Web as a whole. The W3C continues to set standards, which can today be seen with JavaScript and other languages. In 1994 Andreessen formed Mosaic Communications Corp. that later became known as Netscape Communications, the Netscape 0.9 browser. Netscape created its HTML tags without regard to the traditional standards process. For example, Netscape 1.1 included tags for changing background colours and formatting text with tables on web pages. From 1996 to 1999 the browser wars began, as Microsoft and Netscape fought for ultimate browser dominance. During this time there were many new technologies in the field, notably Cascading Style Sheets, JavaScript, and Dynamic HTML. On the whole, the browser competition did lead to many positive creations and helped web design evolve at a rapid pace.[6]

In 1996, Microsoft released its first competitive browser, which was complete with its features and HTML tags. It was also the first browser to support style sheets, which at the time was seen as an obscure authoring technique and is today an important aspect of web design.[6] The HTML markup for tables was originally intended for displaying tabular data. However, designers quickly realized the potential of using HTML tables for creating complex, multi-column layouts that were otherwise not possible. At this time, as design and good aesthetics seemed to take precedence over good markup structure, little attention was paid to semantics and web accessibility. HTML sites were limited in their design options, even more so with earlier versions of HTML. To create complex designs, many web designers had to use complicated table structures or even use blank spacer .GIF images to stop empty table cells from collapsing.[7] CSS was introduced in December 1996 by the W3C to support presentation and layout. This allowed HTML code to be semantic rather than both semantic and presentational and improved web accessibility, see tableless web design.

In 1996, Flash (originally known as FutureSplash) was developed. At the time, the Flash content development tool was relatively simple compared to now, using basic layout and drawing tools, a limited precursor to ActionScript, and a timeline, but it enabled web designers to go beyond the point of HTML, animated GIFs and JavaScript. However, because Flash required a plug-in, many web developers avoided using it for fear of limiting their market share due to lack of compatibility. Instead, designers reverted to GIF animations (if they did not forego using motion graphics altogether) and JavaScript for widgets. But the benefits of Flash made it popular enough among specific target markets to eventually work its way to the vast majority of browsers, and powerful enough to be used to develop entire sites.[7]

In 1998, Netscape released Netscape Communicator code under an open-source licence, enabling thousands of developers to participate in improving the software. However, these developers decided to start a standard for the web from scratch, which guided the development of the open-source browser and soon expanded to a complete application platform.[6] The Web Standards Project was formed and promoted browser compliance with HTML and CSS standards. Programs like Acid1, Acid2, and Acid3 were created in order to test browsers for compliance with web standards. In 2000, Internet Explorer was released for Mac, which was the first browser that fully supported HTML 4.01 and CSS 1. It was also the first browser to fully support the PNG image format.[6] By 2001, after a campaign by Microsoft to popularize Internet Explorer, Internet Explorer had reached 96% of web browser usage share, which signified the end of the first browser wars as Internet Explorer had no real competition.[8]

Since the start of the 21st century, the web has become more and more integrated into people's lives. As this has happened the technology of the web has also moved on. There have also been significant changes in the way people use and access the web, and this has changed how sites are designed.

Since the end of the browsers wars[when?] new browsers have been released. Many of these are open source, meaning that they tend to have faster development and are more supportive of new standards. The new options are considered by many[weasel words] to be better than Microsoft's Internet Explorer.

The W3C has released new standards for HTML (HTML5) and CSS (CSS3), as well as new JavaScript APIs, each as a new but individual standard.[when?] While the term HTML5 is only used to refer to the new version of HTML and some of the JavaScript APIs, it has become common to use it to refer to the entire suite of new standards (HTML5, CSS3 and JavaScript).

With the advancements in 3G and LTE internet coverage, a significant portion of website traffic shifted to mobile devices. This shift influenced the web design industry, steering it towards a minimalist, lighter, and more simplistic style. The "mobile first" approach emerged as a result, emphasizing the creation of website designs that prioritize mobile-oriented layouts first, before adapting them to larger screen dimensions.

Web designers use a variety of different tools depending on what part of the production process they are involved in. These tools are updated over time by newer standards and software but the principles behind them remain the same. Web designers use both vector and raster graphics editors to create web-formatted imagery or design prototypes. A website can be created using WYSIWYG website builder software or a content management system, or the individual web pages can be hand-coded in just the same manner as the first web pages were created. Other tools web designers might use include markup validators[9] and other testing tools for usability and accessibility to ensure their websites meet web accessibility guidelines.[10]

One popular tool in web design is UX Design, a type of art that designs products to perform an accurate user background. UX design is very deep. UX is more than the web, it is very independent, and its fundamentals can be applied to many other browsers or apps. Web design is mostly based on web-based things. UX can overlap both web design and design. UX design mostly focuses on products that are less web-based.[11]

Marketing and communication design on a website may identify what works for its target market. This can be an age group or particular strand of culture; thus the designer may understand the trends of its audience. Designers may also understand the type of website they are designing, meaning, for example, that (B2B) business-to-business website design considerations might differ greatly from a consumer-targeted website such as a retail or entertainment website. Careful consideration might be made to ensure that the aesthetics or overall design of a site do not clash with the clarity and accuracy of the content or the ease of web navigation,[12] especially on a B2B website. Designers may also consider the reputation of the owner or business the site is representing to make sure they are portrayed favorably. Web designers normally oversee all the websites that are made on how they work or operate on things. They constantly are updating and changing everything on websites behind the scenes. All the elements they do are text, photos, graphics, and layout of the web. Before beginning work on a website, web designers normally set an appointment with their clients to discuss layout, colour, graphics, and design. Web designers spend the majority of their time designing websites and making sure the speed is right. Web designers typically engage in testing and working, marketing, and communicating with other designers about laying out the websites and finding the right elements for the websites.[13]

User understanding of the content of a website often depends on user understanding of how the website works. This is part of the user experience design. User experience is related to layout, clear instructions, and labeling on a website. How well a user understands how they can interact on a site may also depend on the interactive design of the site. If a user perceives the usefulness of the website, they are more likely to continue using it. Users who are skilled and well versed in website use may find a more distinctive, yet less intuitive or less user-friendly website interface useful nonetheless. However, users with less experience are less likely to see the advantages or usefulness of a less intuitive website interface. This drives the trend for a more universal user experience and ease of access to accommodate as many users as possible regardless of user skill.[14] Much of the user experience design and interactive design are considered in the user interface design.

Advanced interactive functions may require plug-ins if not advanced coding language skills. Choosing whether or not to use interactivity that requires plug-ins is a critical decision in user experience design. If the plug-in doesn't come pre-installed with most browsers, there's a risk that the user will have neither the know-how nor the patience to install a plug-in just to access the content. If the function requires advanced coding language skills, it may be too costly in either time or money to code compared to the amount of enhancement the function will add to the user experience. There's also a risk that advanced interactivity may be incompatible with older browsers or hardware configurations. Publishing a function that doesn't work reliably is potentially worse for the user experience than making no attempt. It depends on the target audience if it's likely to be needed or worth any risks.

Progressive enhancement is a strategy in web design that puts emphasis on web content first, allowing everyone to access the basic content and functionality of a web page, whilst users with additional browser features or faster Internet access receive the enhanced version instead.

In practice, this means serving content through HTML and applying styling and animation through CSS to the technically possible extent, then applying further enhancements through JavaScript. Pages' text is loaded immediately through the HTML source code rather than having to wait for JavaScript to initiate and load the content subsequently, which allows content to be readable with minimum loading time and bandwidth, and through text-based browsers, and maximizes backwards compatibility.[15]

As an example, MediaWiki-based sites including Wikipedia use progressive enhancement, as they remain usable while JavaScript and even CSS is deactivated, as pages' content is included in the page's HTML source code, whereas counter-example Everipedia relies on JavaScript to load pages' content subsequently; a blank page appears with JavaScript deactivated.

Part of the user interface design is affected by the quality of the page layout. For example, a designer may consider whether the site's page layout should remain consistent on different pages when designing the layout. Page pixel width may also be considered vital for aligning objects in the layout design. The most popular fixed-width websites generally have the same set width to match the current most popular browser window, at the current most popular screen resolution, on the current most popular monitor size. Most pages are also center-aligned for concerns of aesthetics on larger screens.

Fluid layouts increased in popularity around 2000 to allow the browser to make user-specific layout adjustments to fluid layouts based on the details of the reader's screen (window size, font size relative to window, etc.). They grew as an alternative to HTML-table-based layouts and grid-based design in both page layout design principles and in coding technique but were very slow to be adopted.[note 1] This was due to considerations of screen reading devices and varying windows sizes which designers have no control over. Accordingly, a design may be broken down into units (sidebars, content blocks, embedded advertising areas, navigation areas) that are sent to the browser and which will be fitted into the display window by the browser, as best it can. Although such a display may often change the relative position of major content units, sidebars may be displaced below body text rather than to the side of it. This is a more flexible display than a hard-coded grid-based layout that doesn't fit the device window. In particular, the relative position of content blocks may change while leaving the content within the block unaffected. This also minimizes the user's need to horizontally scroll the page.

Responsive web design is a newer approach, based on CSS3, and a deeper level of per-device specification within the page's style sheet through an enhanced use of the CSS @media rule. In March 2018 Google announced they would be rolling out mobile-first indexing.[16] Sites using responsive design are well placed to ensure they meet this new approach.

Web designers may choose to limit the variety of website typefaces to only a few which are of a similar style, instead of using a wide range of typefaces or type styles. Most browsers recognize a specific number of safe fonts, which designers mainly use in order to avoid complications.

Font downloading was later included in the CSS3 fonts module and has since been implemented in Safari 3.1, Opera 10, and Mozilla Firefox 3.5. This has subsequently increased interest in web typography, as well as the usage of font downloading.

Most site layouts incorporate negative space to break the text up into paragraphs and also avoid center-aligned text.[17]

The page layout and user interface may also be affected by the use of motion graphics. The choice of whether or not to use motion graphics may depend on the target market for the website. Motion graphics may be expected or at least better received with an entertainment-oriented website. However, a website target audience with a more serious or formal interest (such as business, community, or government) might find animations unnecessary and distracting if only for entertainment or decoration purposes. This doesn't mean that more serious content couldn't be enhanced with animated or video presentations that is relevant to the content. In either case, motion graphic design may make the difference between more effective visuals or distracting visuals.

Motion graphics that are not initiated by the site visitor can produce accessibility issues. The World Wide Web consortium accessibility standards require that site visitors be able to disable the animations.[18]

Website designers may consider it to be good practice to conform to standards. This is usually done via a description specifying what the element is doing. Failure to conform to standards may not make a website unusable or error-prone, but standards can relate to the correct layout of pages for readability as well as making sure coded elements are closed appropriately. This includes errors in code, a more organized layout for code, and making sure IDs and classes are identified properly. Poorly coded pages are sometimes colloquially called tag soup. Validating via W3C[9] can only be done when a correct DOCTYPE declaration is made, which is used to highlight errors in code. The system identifies the errors and areas that do not conform to web design standards. This information can then be corrected by the user.[19]

There are two ways websites are generated: statically or dynamically.

A static website stores a unique file for every page of a static website. Each time that page is requested, the same content is returned. This content is created once, during the design of the website. It is usually manually authored, although some sites use an automated creation process, similar to a dynamic website, whose results are stored long-term as completed pages. These automatically created static sites became more popular around 2015, with generators such as Jekyll and Adobe Muse.[20]

The benefits of a static website are that they were simpler to host, as their server only needed to serve static content, not execute server-side scripts. This required less server administration and had less chance of exposing security holes. They could also serve pages more quickly, on low-cost server hardware. This advantage became less important as cheap web hosting expanded to also offer dynamic features, and virtual servers offered high performance for short intervals at low cost.

Almost all websites have some static content, as supporting assets such as images and style sheets are usually static, even on a website with highly dynamic pages.

Dynamic websites are generated on the fly and use server-side technology to generate web pages. They typically extract their content from one or more back-end databases: some are database queries across a relational database to query a catalog or to summarise numeric information, and others may use a document database such as MongoDB or NoSQL to store larger units of content, such as blog posts or wiki articles.

In the design process, dynamic pages are often mocked-up or wireframed using static pages. The skillset needed to develop dynamic web pages is much broader than for a static page, involving server-side and database coding as well as client-side interface design. Even medium-sized dynamic projects are thus almost always a team effort.

When dynamic web pages first developed, they were typically coded directly in languages such as Perl, PHP or ASP. Some of these, notably PHP and ASP, used a 'template' approach where a server-side page resembled the structure of the completed client-side page, and data was inserted into places defined by 'tags'. This was a quicker means of development than coding in a purely procedural coding language such as Perl.

Both of these approaches have now been supplanted for many websites by higher-level application-focused tools such as content management systems. These build on top of general-purpose coding platforms and assume that a website exists to offer content according to one of several well-recognised models, such as a time-sequenced blog, a thematic magazine or news site, a wiki, or a user forum. These tools make the implementation of such a site very easy, and a purely organizational and design-based task, without requiring any coding.

Editing the content itself (as well as the template page) can be done both by means of the site itself and with the use of third-party software. The ability to edit all pages is provided only to a specific category of users (for example, administrators, or registered users). In some cases, anonymous users are allowed to edit certain web content, which is less frequent (for example, on forums - adding messages). An example of a site with an anonymous change is Wikipedia.

Usability experts, including Jakob Nielsen and Kyle Soucy, have often emphasised homepage design for website success and asserted that the homepage is the most important page on a website.[21] Nielsen, Jakob; Tahir, Marie (October 2001), Homepage Usability: 50 Websites Deconstructed, New Riders Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7357-1102-0[22][23] However practitioners into the 2000s were starting to find that a growing number of website traffic was bypassing the homepage, going directly to internal content pages through search engines, e-newsletters and RSS feeds.[24] This led many practitioners to argue that homepages are less important than most people think.[25][26][27][28] Jared Spool argued in 2007 that a site's homepage was actually the least important page on a website.[29]

In 2012 and 2013, carousels (also called 'sliders' and 'rotating banners') have become an extremely popular design element on homepages, often used to showcase featured or recent content in a confined space.[30] Many practitioners argue that carousels are an ineffective design element and hurt a website's search engine optimisation and usability.[30][31][32]

There are two primary jobs involved in creating a website: the web designer and web developer, who often work closely together on a website.[33] The web designers are responsible for the visual aspect, which includes the layout, colouring, and typography of a web page. Web designers will also have a working knowledge of markup languages such as HTML and CSS, although the extent of their knowledge will differ from one web designer to another. Particularly in smaller organizations, one person will need the necessary skills for designing and programming the full web page, while larger organizations may have a web designer responsible for the visual aspect alone.

Further jobs which may become involved in the creation of a website include:

Chat GPT and other AI models are being used to write and code websites making it faster and easier to create websites. There are still discussions about the ethical implications on using artificial intelligence for design as the world becomes more familiar with using AI for time-consuming tasks used in design processes.[34]

<table>-based markup and spacer .GIF imagescite web: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)cite web: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

| Semantics | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||

| Semantics of programming languages |

||||||||

|

||||||||

The Semantic Web, sometimes known as Web 3.0 (not to be confused with Web3), is an extension of the World Wide Web through standards[1] set by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). The goal of the Semantic Web is to make Internet data machine-readable.

To enable the encoding of semantics with the data, technologies such as Resource Description Framework (RDF)[2] and Web Ontology Language (OWL)[3] are used. These technologies are used to formally represent metadata. For example, ontology can describe concepts, relationships between entities, and categories of things. These embedded semantics offer significant advantages such as reasoning over data and operating with heterogeneous data sources.[4] These standards promote common data formats and exchange protocols on the Web, fundamentally the RDF. According to the W3C, "The Semantic Web provides a common framework that allows data to be shared and reused across application, enterprise, and community boundaries."[5] The Semantic Web is therefore regarded as an integrator across different content and information applications and systems.

The term was coined by Tim Berners-Lee for a web of data (or data web)[6] that can be processed by machines[7]—that is, one in which much of the meaning is machine-readable. While its critics have questioned its feasibility, proponents argue that applications in library and information science, industry, biology and human sciences research have already proven the validity of the original concept.[8]

Berners-Lee originally expressed his vision of the Semantic Web in 1999 as follows:

I have a dream for the Web [in which computers] become capable of analyzing all the data on the Web – the content, links, and transactions between people and computers. A "Semantic Web", which makes this possible, has yet to emerge, but when it does, the day-to-day mechanisms of trade, bureaucracy and our daily lives will be handled by machines talking to machines. The "intelligent agents" people have touted for ages will finally materialize.[9]

The 2001 Scientific American article by Berners-Lee, Hendler, and Lassila described an expected evolution of the existing Web to a Semantic Web.[10] In 2006, Berners-Lee and colleagues stated that: "This simple idea…remains largely unrealized".[11] In 2013, more than four million Web domains (out of roughly 250 million total) contained Semantic Web markup.[12]

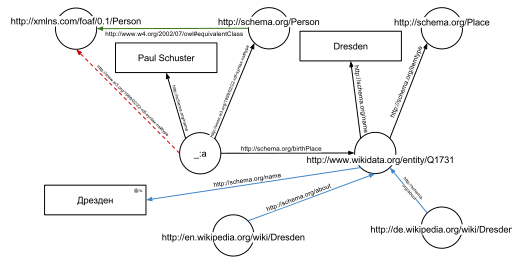

In the following example, the text "Paul Schuster was born in Dresden" on a website will be annotated, connecting a person with their place of birth. The following HTML fragment shows how a small graph is being described, in RDFa-syntax using a schema.org vocabulary and a Wikidata ID:

<div vocab="https://schema.org/" typeof="Person">

<span property="name">Paul Schuster</span> was born in

<span property="birthPlace" typeof="Place" href="https://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q1731">

<span property="name">Dresden</span>.

</span>

</div>

The example defines the following five triples (shown in Turtle syntax). Each triple represents one edge in the resulting graph: the first element of the triple (the subject) is the name of the node where the edge starts, the second element (the predicate) the type of the edge, and the last and third element (the object) either the name of the node where the edge ends or a literal value (e.g. a text, a number, etc.).

_:a <https://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#type> <https://schema.org/Person> .

_:a <https://schema.org/name> "Paul Schuster" .

_:a <https://schema.org/birthPlace> <https://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q1731> .

<https://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q1731> <https://schema.org/itemtype> <https://schema.org/Place> .

<https://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q1731> <https://schema.org/name> "Dresden" .

The triples result in the graph shown in the given figure.

One of the advantages of using Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs) is that they can be dereferenced using the HTTP protocol. According to the so-called Linked Open Data principles, such a dereferenced URI should result in a document that offers further data about the given URI. In this example, all URIs, both for edges and nodes (e.g. http://schema.org/Person, http://schema.org/birthPlace, http://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q1731) can be dereferenced and will result in further RDF graphs, describing the URI, e.g. that Dresden is a city in Germany, or that a person, in the sense of that URI, can be fictional.

The second graph shows the previous example, but now enriched with a few of the triples from the documents that result from dereferencing https://schema.org/Person (green edge) and https://www.wikidata.org/entity/Q1731 (blue edges).

Additionally to the edges given in the involved documents explicitly, edges can be automatically inferred: the triple

_:a <https://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#type> <http://schema.org/Person> .

from the original RDFa fragment and the triple

<https://schema.org/Person> <http://www.w3.org/2002/07/owl#equivalentClass> <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/Person> .

from the document at https://schema.org/Person (green edge in the figure) allow to infer the following triple, given OWL semantics (red dashed line in the second Figure):

_:a <https://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#type> <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/Person> .

The concept of the semantic network model was formed in the early 1960s by researchers such as the cognitive scientist Allan M. Collins, linguist Ross Quillian and psychologist Elizabeth F. Loftus as a form to represent semantically structured knowledge. When applied in the context of the modern internet, it extends the network of hyperlinked human-readable web pages by inserting machine-readable metadata about pages and how they are related to each other. This enables automated agents to access the Web more intelligently and perform more tasks on behalf of users. The term "Semantic Web" was coined by Tim Berners-Lee,[7] the inventor of the World Wide Web and director of the World Wide Web Consortium ("W3C"), which oversees the development of proposed Semantic Web standards. He defines the Semantic Web as "a web of data that can be processed directly and indirectly by machines".

Many of the technologies proposed by the W3C already existed before they were positioned under the W3C umbrella. These are used in various contexts, particularly those dealing with information that encompasses a limited and defined domain, and where sharing data is a common necessity, such as scientific research or data exchange among businesses. In addition, other technologies with similar goals have emerged, such as microformats.

Many files on a typical computer can be loosely divided into either human-readable documents, or machine-readable data. Examples of human-readable document files are mail messages, reports, and brochures. Examples of machine-readable data files are calendars, address books, playlists, and spreadsheets, which are presented to a user using an application program that lets the files be viewed, searched, and combined.

Currently, the World Wide Web is based mainly on documents written in Hypertext Markup Language (HTML), a markup convention that is used for coding a body of text interspersed with multimedia objects such as images and interactive forms. Metadata tags provide a method by which computers can categorize the content of web pages. In the examples below, the field names "keywords", "description" and "author" are assigned values such as "computing", and "cheap widgets for sale" and "John Doe".

<meta name="keywords" content="computing, computer studies, computer" />

<meta name="description" content="Cheap widgets for sale" />

<meta name="author" content="John Doe" />

Because of this metadata tagging and categorization, other computer systems that want to access and share this data can easily identify the relevant values.

With HTML and a tool to render it (perhaps web browser software, perhaps another user agent), one can create and present a page that lists items for sale. The HTML of this catalog page can make simple, document-level assertions such as "this document's title is 'Widget Superstore'", but there is no capability within the HTML itself to assert unambiguously that, for example, item number X586172 is an Acme Gizmo with a retail price of €199, or that it is a consumer product. Rather, HTML can only say that the span of text "X586172" is something that should be positioned near "Acme Gizmo" and "€199", etc. There is no way to say "this is a catalog" or even to establish that "Acme Gizmo" is a kind of title or that "€199" is a price. There is also no way to express that these pieces of information are bound together in describing a discrete item, distinct from other items perhaps listed on the page.

Semantic HTML refers to the traditional HTML practice of markup following intention, rather than specifying layout details directly. For example, the use of <em> denoting "emphasis" rather than <i>, which specifies italics. Layout details are left up to the browser, in combination with Cascading Style Sheets. But this practice falls short of specifying the semantics of objects such as items for sale or prices.

Microformats extend HTML syntax to create machine-readable semantic markup about objects including people, organizations, events and products.[13] Similar initiatives include RDFa, Microdata and Schema.org.

The Semantic Web takes the solution further. It involves publishing in languages specifically designed for data: Resource Description Framework (RDF), Web Ontology Language (OWL), and Extensible Markup Language (XML). HTML describes documents and the links between them. RDF, OWL, and XML, by contrast, can describe arbitrary things such as people, meetings, or airplane parts.

These technologies are combined in order to provide descriptions that supplement or replace the content of Web documents. Thus, content may manifest itself as descriptive data stored in Web-accessible databases,[14] or as markup within documents (particularly, in Extensible HTML (XHTML) interspersed with XML, or, more often, purely in XML, with layout or rendering cues stored separately). The machine-readable descriptions enable content managers to add meaning to the content, i.e., to describe the structure of the knowledge we have about that content. In this way, a machine can process knowledge itself, instead of text, using processes similar to human deductive reasoning and inference, thereby obtaining more meaningful results and helping computers to perform automated information gathering and research.

An example of a tag that would be used in a non-semantic web page:

<item>blog</item>

Encoding similar information in a semantic web page might look like this:

<item rdf:about="https://example.org/semantic-web/">Semantic Web</item>

Tim Berners-Lee calls the resulting network of Linked Data the Giant Global Graph, in contrast to the HTML-based World Wide Web. Berners-Lee posits that if the past was document sharing, the future is data sharing. His answer to the question of "how" provides three points of instruction. One, a URL should point to the data. Two, anyone accessing the URL should get data back. Three, relationships in the data should point to additional URLs with data.

Tags, including hierarchical categories and tags that are collaboratively added and maintained (e.g. with folksonomies) can be considered part of, of potential use to or a step towards the semantic Web vision.[15][16][17]

Unique identifiers, including hierarchical categories and collaboratively added ones, analysis tools and metadata, including tags, can be used to create forms of semantic webs – webs that are to a certain degree semantic.[18] In particular, such has been used for structuring scientific research i.a. by research topics and scientific fields by the projects OpenAlex,[19][20][21] Wikidata and Scholia which are under development and provide APIs, Web-pages, feeds and graphs for various semantic queries.

Tim Berners-Lee has described the Semantic Web as a component of Web 3.0.[22]

People keep asking what Web 3.0 is. I think maybe when you've got an overlay of scalable vector graphics – everything rippling and folding and looking misty – on Web 2.0 and access to a semantic Web integrated across a huge space of data, you'll have access to an unbelievable data resource …

— Tim Berners-Lee, 2006

"Semantic Web" is sometimes used as a synonym for "Web 3.0",[23] though the definition of each term varies.

The next generation of the Web is often termed Web 4.0, but its definition is not clear. According to some sources, it is a Web that involves artificial intelligence,[24] the internet of things, pervasive computing, ubiquitous computing and the Web of Things among other concepts.[25] According to the European Union, Web 4.0 is "the expected fourth generation of the World Wide Web. Using advanced artificial and ambient intelligence, the internet of things, trusted blockchain transactions, virtual worlds and XR capabilities, digital and real objects and environments are fully integrated and communicate with each other, enabling truly intuitive, immersive experiences, seamlessly blending the physical and digital worlds".[26]

Some of the challenges for the Semantic Web include vastness, vagueness, uncertainty, inconsistency, and deceit. Automated reasoning systems will have to deal with all of these issues in order to deliver on the promise of the Semantic Web.

This list of challenges is illustrative rather than exhaustive, and it focuses on the challenges to the "unifying logic" and "proof" layers of the Semantic Web. The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) Incubator Group for Uncertainty Reasoning for the World Wide Web[27] (URW3-XG) final report lumps these problems together under the single heading of "uncertainty".[28] Many of the techniques mentioned here will require extensions to the Web Ontology Language (OWL) for example to annotate conditional probabilities. This is an area of active research.[29]

Standardization for Semantic Web in the context of Web 3.0 is under the care of W3C.[30]

The term "Semantic Web" is often used more specifically to refer to the formats and technologies that enable it.[5] The collection, structuring and recovery of linked data are enabled by technologies that provide a formal description of concepts, terms, and relationships within a given knowledge domain. These technologies are specified as W3C standards and include:

The Semantic Web Stack illustrates the architecture of the Semantic Web. The functions and relationships of the components can be summarized as follows:[31]

Well-established standards:

Not yet fully realized:

The intent is to enhance the usability and usefulness of the Web and its interconnected resources by creating semantic web services, such as:

<meta> tags used in today's Web pages to supply information for Web search engines using web crawlers). This could be machine-understandable information about the human-understandable content of the document (such as the creator, title, description, etc.) or it could be purely metadata representing a set of facts (such as resources and services elsewhere on the site). Note that anything that can be identified with a Uniform Resource Identifier (URI) can be described, so the semantic web can reason about animals, people, places, ideas, etc. There are four semantic annotation formats that can be used in HTML documents; Microformat, RDFa, Microdata and JSON-LD.[35] Semantic markup is often generated automatically, rather than manually.

Such services could be useful to public search engines, or could be used for knowledge management within an organization. Business applications include:

In a corporation, there is a closed group of users and the management is able to enforce company guidelines like the adoption of specific ontologies and use of semantic annotation. Compared to the public Semantic Web there are lesser requirements on scalability and the information circulating within a company can be more trusted in general; privacy is less of an issue outside of handling of customer data.

Critics question the basic feasibility of a complete or even partial fulfillment of the Semantic Web, pointing out both difficulties in setting it up and a lack of general-purpose usefulness that prevents the required effort from being invested. In a 2003 paper, Marshall and Shipman point out the cognitive overhead inherent in formalizing knowledge, compared to the authoring of traditional web hypertext:[46]

While learning the basics of HTML is relatively straightforward, learning a knowledge representation language or tool requires the author to learn about the representation's methods of abstraction and their effect on reasoning. For example, understanding the class-instance relationship, or the superclass-subclass relationship, is more than understanding that one concept is a "type of" another concept. [...] These abstractions are taught to computer scientists generally and knowledge engineers specifically but do not match the similar natural language meaning of being a "type of" something. Effective use of such a formal representation requires the author to become a skilled knowledge engineer in addition to any other skills required by the domain. [...] Once one has learned a formal representation language, it is still often much more effort to express ideas in that representation than in a less formal representation [...]. Indeed, this is a form of programming based on the declaration of semantic data and requires an understanding of how reasoning algorithms will interpret the authored structures.

According to Marshall and Shipman, the tacit and changing nature of much knowledge adds to the knowledge engineering problem, and limits the Semantic Web's applicability to specific domains. A further issue that they point out are domain- or organization-specific ways to express knowledge, which must be solved through community agreement rather than only technical means.[46] As it turns out, specialized communities and organizations for intra-company projects have tended to adopt semantic web technologies greater than peripheral and less-specialized communities.[47] The practical constraints toward adoption have appeared less challenging where domain and scope is more limited than that of the general public and the World-Wide Web.[47]

Finally, Marshall and Shipman see pragmatic problems in the idea of (Knowledge Navigator-style) intelligent agents working in the largely manually curated Semantic Web:[46]

In situations in which user needs are known and distributed information resources are well described, this approach can be highly effective; in situations that are not foreseen and that bring together an unanticipated array of information resources, the Google approach is more robust. Furthermore, the Semantic Web relies on inference chains that are more brittle; a missing element of the chain results in a failure to perform the desired action, while the human can supply missing pieces in a more Google-like approach. [...] cost-benefit tradeoffs can work in favor of specially-created Semantic Web metadata directed at weaving together sensible well-structured domain-specific information resources; close attention to user/customer needs will drive these federations if they are to be successful.

Cory Doctorow's critique ("metacrap")[48] is from the perspective of human behavior and personal preferences. For example, people may include spurious metadata into Web pages in an attempt to mislead Semantic Web engines that naively assume the metadata's veracity. This phenomenon was well known with metatags that fooled the Altavista ranking algorithm into elevating the ranking of certain Web pages: the Google indexing engine specifically looks for such attempts at manipulation. Peter Gärdenfors and Timo Honkela point out that logic-based semantic web technologies cover only a fraction of the relevant phenomena related to semantics.[49][50]

Enthusiasm about the semantic web could be tempered by concerns regarding censorship and privacy. For instance, text-analyzing techniques can now be easily bypassed by using other words, metaphors for instance, or by using images in place of words. An advanced implementation of the semantic web would make it much easier for governments to control the viewing and creation of online information, as this information would be much easier for an automated content-blocking machine to understand. In addition, the issue has also been raised that, with the use of FOAF files and geolocation meta-data, there would be very little anonymity associated with the authorship of articles on things such as a personal blog. Some of these concerns were addressed in the "Policy Aware Web" project[51] and is an active research and development topic.

Another criticism of the semantic web is that it would be much more time-consuming to create and publish content because there would need to be two formats for one piece of data: one for human viewing and one for machines. However, many web applications in development are addressing this issue by creating a machine-readable format upon the publishing of data or the request of a machine for such data. The development of microformats has been one reaction to this kind of criticism. Another argument in defense of the feasibility of semantic web is the likely falling price of human intelligence tasks in digital labor markets, such as Amazon's Mechanical Turk.[citation needed]

Specifications such as eRDF and RDFa allow arbitrary RDF data to be embedded in HTML pages. The GRDDL (Gleaning Resource Descriptions from Dialects of Language) mechanism allows existing material (including microformats) to be automatically interpreted as RDF, so publishers only need to use a single format, such as HTML.

The first research group explicitly focusing on the Corporate Semantic Web was the ACACIA team at INRIA-Sophia-Antipolis, founded in 2002. Results of their work include the RDF(S) based Corese[52] search engine, and the application of semantic web technology in the realm of distributed artificial intelligence for knowledge management (e.g. ontologies and multi-agent systems for corporate semantic Web) [53] and E-learning.[54]

Since 2008, the Corporate Semantic Web research group, located at the Free University of Berlin, focuses on building blocks: Corporate Semantic Search, Corporate Semantic Collaboration, and Corporate Ontology Engineering.[55]

Ontology engineering research includes the question of how to involve non-expert users in creating ontologies and semantically annotated content[56] and for extracting explicit knowledge from the interaction of users within enterprises.

Tim O'Reilly, who coined the term Web 2.0, proposed a long-term vision of the Semantic Web as a web of data, where sophisticated applications are navigating and manipulating it.[57] The data web transforms the World Wide Web from a distributed file system into a distributed database.[58]

cite journal: Cite journal requires |journal= (help)cite book: |work= ignored (help)

| Part of a series on |

| Internet marketing |

|---|

| Search engine marketing |

| Display advertising |

| Affiliate marketing |

| Mobile advertising |

Local search engine optimization (local SEO) is similar to (national) SEO in that it is also a process affecting the visibility of a website or a web page in a web search engine's unpaid results (known as its SERP, search engine results page) often referred to as "natural", "organic", or "earned" results.[1] In general, the higher ranked on the search results page and more frequently a site appears in the search results list, the more visitors it will receive from the search engine's users; these visitors can then be converted into customers.[2] Local SEO, however, differs in that it is focused on optimizing a business's online presence so that its web pages will be displayed by search engines when users enter local searches for its products or services.[3] Ranking for local search involves a similar process to general SEO but includes some specific elements to rank a business for local search.

For example, local SEO is all about 'optimizing' your online presence to attract more business from relevant local searches. The majority of these searches take place on Google, Yahoo, Bing, Yandex, Baidu and other search engines but for better optimization in your local area you should also use sites like Yelp, Angie's List, LinkedIn, Local business directories, social media channels and others.[4]

The origin of local SEO can be traced back[5] to 2003-2005 when search engines tried to provide people with results in their vicinity as well as additional information such as opening times of a store, listings in maps, etc.

Local SEO has evolved over the years to provide a targeted online marketing approach that allows local businesses to appear based on a range of local search signals, providing a distinct difference from broader organic SEO which prioritises relevance of search over a distance of searcher.

Local searches trigger search engines to display two types of results on the Search engine results page: local organic results and the 'Local Pack'.[3] The local organic results include web pages related to the search query with local relevance. These often include directories such as Yelp, Yellow Pages, Facebook, etc.[3] The Local Pack displays businesses that have signed up with Google and taken ownership of their 'Google My Business' (GMB) listing.

The information displayed in the GMB listing and hence in the Local Pack can come from different sources:[6]

Depending on the searches, Google can show relevant local results in Google Maps or Search. This is true on both mobile and desktop devices.[7]

Google has added a new Q&A features to Google Maps allowing users to submit questions to owners and allowing these to respond.[8] This Q&A feature is tied to the associated Google My Business account.

Google Business Profile (GBP), formerly Google My Business (GMB) is a free tool that allows businesses to create and manage their Google Business listing. These listings must represent a physical location that a customer can visit. A Google Business listing appears when customers search for businesses either on Google Maps or in Google SERPs. The accuracy of these listings is a local ranking factor.

Major search engines have algorithms that determine which local businesses rank in local search. Primary factors that impact a local business's chance of appearing in local search include proper categorization in business directories, a business's name, address, and phone number (NAP) being crawlable on the website, and citations (mentions of the local business on other relevant websites like a chamber of commerce website).[9]

In 2016, a study using statistical analysis assessed how and why businesses ranked in the Local Packs and identified positive correlations between local rankings and 100+ ranking factors.[10] Although the study cannot replicate Google's algorithm, it did deliver several interesting findings:

Prominence, relevance, and distance are the three main criteria Google claims to use in its algorithms to show results that best match a user's query.[12]

According to a group of local SEO experts who took part in a survey, links and reviews are more important than ever to rank locally.[13]

As a result of both Google as well as Apple offering "near me" as an option to users, some authors[14] report on how Google Trends shows very significant increases in "near me" queries. The same authors also report that the factors correlating the most with Local Pack ranking for "near me" queries include the presence of the "searched city and state in backlinks' anchor text" as well as the use of the " 'near me' in internal link anchor text"

An important update to Google's local algorithm, rolled out on the 1st of September 2016.[15] Summary of the update on local search results:

As previously explained (see above), the Possum update led similar listings, within the same building, or even located on the same street, to get filtered. As a result, only one listing "with greater organic ranking and stronger relevance to the keyword" would be shown.[16] After the Hawk update on 22 August 2017, this filtering seems to apply only to listings located within the same building or close by (e.g. 50 feet), but not to listings located further away (e.g.325 feet away).[16]

As previously explained (see above), reviews are deemed to be an important ranking factor. Joy Hawkins, a Google Top Contributor and local SEO expert, highlights the problems due to fake reviews:[17]