Maximise your business potential with SEO tracking and reporting Parramatta We deliver impactful strategies designed to boost your brand awareness, improve online visibility, and generate a steady flow of qualified leads in Parramatta

Transform your business growth with Full-service web design Parramatta Our strategies enhance visibility, attract targeted traffic, and maximise conversions for sustained success Partner with us for measurable digital marketing outcomes today

Maximise your business potential with Affordable digital marketing Parramatta We deliver impactful strategies designed to boost your brand awareness, improve online visibility, and generate a steady flow of qualified leads in Parramatta

Web Design Parramatta .Choose excellence in digital marketing with SEO services in Parramatta Our proven approaches drive website traffic, enhance customer engagement, and significantly improve conversion rates, supporting long-term business success in Parramatta

Maximise your business potential with Parramatta website redesign We deliver impactful strategies designed to boost your brand awareness, improve online visibility, and generate a steady flow of qualified leads in Parramatta

Maximise your business potential with Best web designers in Parramatta We deliver impactful strategies designed to boost your brand awareness, improve online visibility, and generate a steady flow of qualified leads in Parramatta

Effective Local SEO Sydney.Choose excellence in digital marketing with Parramatta SEO digital experts Our proven approaches drive website traffic, enhance customer engagement, and significantly improve conversion rates, supporting long-term business success in Parramatta

Transform your business growth with Web design for local business Parramatta Our strategies enhance visibility, attract targeted traffic, and maximise conversions for sustained success Partner with us for measurable digital marketing outcomes today

Experience outstanding online performance through Parramatta SEO optimisation Our expert team specialises in delivering solutions that improve rankings, drive engagement, and generate valuable leads for consistent business growth in Parramatta

Best SEO Packages Parramatta Parramatta.

Maximise your business potential with Parramatta SEO for eCommerce We deliver impactful strategies designed to boost your brand awareness, improve online visibility, and generate a steady flow of qualified leads in Parramatta

Transform your business growth with Web design SEO integration Parramatta Our strategies enhance visibility, attract targeted traffic, and maximise conversions for sustained success Partner with us for measurable digital marketing outcomes today

Transform your business growth with Advanced SEO strategies Parramatta Our strategies enhance visibility, attract targeted traffic, and maximise conversions for sustained success Partner with us for measurable digital marketing outcomes today

Experience outstanding online performance through Custom website packages Parramatta Our expert team specialises in delivering solutions that improve rankings, drive engagement, and generate valuable leads for consistent business growth in Parramatta

Take your digital presence further with SEO campaigns Parramatta We develop custom strategies aimed at increasing your online visibility, improving search engine rankings, and achieving sustainable growth for your Parramatta-based business

Experience outstanding online performance through Parramatta online marketing Our expert team specialises in delivering solutions that improve rankings, drive engagement, and generate valuable leads for consistent business growth in Parramatta

Maximise your business potential with Web hosting and design Parramatta We deliver impactful strategies designed to boost your brand awareness, improve online visibility, and generate a steady flow of qualified leads in Parramatta

Choose excellence in digital marketing with Affordable website packages Parramatta Our proven approaches drive website traffic, enhance customer engagement, and significantly improve conversion rates, supporting long-term business success in Parramatta

Experience outstanding online performance through WordPress SEO Parramatta Our expert team specialises in delivering solutions that improve rankings, drive engagement, and generate valuable leads for consistent business growth in Parramatta

Experience outstanding online performance through SEO copywriting Parramatta Our expert team specialises in delivering solutions that improve rankings, drive engagement, and generate valuable leads for consistent business growth in Parramatta

Choose excellence in digital marketing with Professional web developers Parramatta Our proven approaches drive website traffic, enhance customer engagement, and significantly improve conversion rates, supporting long-term business success in Parramatta

Transform your business growth with Parramatta website speed optimisation Our strategies enhance visibility, attract targeted traffic, and maximise conversions for sustained success Partner with us for measurable digital marketing outcomes today

In the Internet, a domain name is a string that identifies a realm of administrative autonomy, authority or control. Domain names are often used to identify services provided through the Internet, such as websites, email services and more. Domain names are used in various networking contexts and for application-specific naming and addressing purposes. In general, a domain name identifies a network domain or an Internet Protocol (IP) resource, such as a personal computer used to access the Internet, or a server computer.

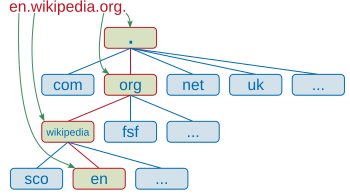

Domain names are formed by the rules and procedures of the Domain Name System (DNS). Any name registered in the DNS is a domain name. Domain names are organized in subordinate levels (subdomains) of the DNS root domain, which is nameless. The first-level set of domain names are the top-level domains (TLDs), including the generic top-level domains (gTLDs), such as the prominent domains com, info, net, edu, and org, and the country code top-level domains (ccTLDs). Below these top-level domains in the DNS hierarchy are the second-level and third-level domain names that are typically open for reservation by end-users who wish to connect local area networks to the Internet, create other publicly accessible Internet resources or run websites, such as "wikipedia.org". The registration of a second- or third-level domain name is usually administered by a domain name registrar who sell its services to the public.

A fully qualified domain name (FQDN) is a domain name that is completely specified with all labels in the hierarchy of the DNS, having no parts omitted. Traditionally a FQDN ends in a dot (.) to denote the top of the DNS tree.[1] Labels in the Domain Name System are case-insensitive, and may therefore be written in any desired capitalization method, but most commonly domain names are written in lowercase in technical contexts.[2] A hostname is a domain name that has at least one associated IP address.

Domain names serve to identify Internet resources, such as computers, networks, and services, with a text-based label that is easier to memorize than the numerical addresses used in the Internet protocols. A domain name may represent entire collections of such resources or individual instances. Individual Internet host computers use domain names as host identifiers, also called hostnames. The term hostname is also used for the leaf labels in the domain name system, usually without further subordinate domain name space. Hostnames appear as a component in Uniform Resource Locators (URLs) for Internet resources such as websites (e.g., en.wikipedia.org).

Domain names are also used as simple identification labels to indicate ownership or control of a resource. Such examples are the realm identifiers used in the Session Initiation Protocol (SIP), the Domain Keys used to verify DNS domains in e-mail systems, and in many other Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs).

An important function of domain names is to provide easily recognizable and memorizable names to numerically addressed Internet resources. This abstraction allows any resource to be moved to a different physical location in the address topology of the network, globally or locally in an intranet. Such a move usually requires changing the IP address of a resource and the corresponding translation of this IP address to and from its domain name.

Domain names are used to establish a unique identity. Organizations can choose a domain name that corresponds to their name, helping Internet users to reach them easily.

A generic domain is a name that defines a general category, rather than a specific or personal instance, for example, the name of an industry, rather than a company name. Some examples of generic names are books.com, music.com, and travel.info. Companies have created brands based on generic names, and such generic domain names may be valuable.[3]

Domain names are often simply referred to as domains and domain name registrants are frequently referred to as domain owners, although domain name registration with a registrar does not confer any legal ownership of the domain name, only an exclusive right of use for a particular duration of time. The use of domain names in commerce may subject them to trademark law.

The practice of using a simple memorable abstraction of a host's numerical address on a computer network dates back to the ARPANET era, before the advent of today's commercial Internet. In the early network, each computer on the network retrieved the hosts file (host.txt) from a computer at SRI (now SRI International),[4][5] which mapped computer hostnames to numerical addresses. The rapid growth of the network made it impossible to maintain a centrally organized hostname registry and in 1983 the Domain Name System was introduced on the ARPANET and published by the Internet Engineering Task Force as RFC 882 and RFC 883.

The following table shows the first five .com domains with the dates of their registration:[6]

| Domain name | Registration date |

|---|---|

| symbolics.com | 15 March 1985 |

| bbn.com | 24 April 1985 |

| think.com | 24 May 1985 |

| mcc.com | 11 July 1985 |

| dec.com | 30 September 1985 |

and the first five .edu domains:[7]

| Domain name | Registration date |

|---|---|

| berkeley.edu | 24 April 1985 |

| cmu.edu | 24 April 1985 |

| purdue.edu | 24 April 1985 |

| rice.edu | 24 April 1985 |

| ucla.edu | 24 April 1985 |

Today, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) manages the top-level development and architecture of the Internet domain name space. It authorizes domain name registrars, through which domain names may be registered and reassigned.

The domain name space consists of a tree of domain names. Each node in the tree holds information associated with the domain name. The tree sub-divides into zones beginning at the DNS root zone.

A domain name consists of one or more parts, technically called labels, that are conventionally concatenated, and delimited by dots, such as example.com.

When the Domain Name System was devised in the 1980s, the domain name space was divided into two main groups of domains.[9] The country code top-level domains (ccTLD) were primarily based on the two-character territory codes of ISO-3166 country abbreviations. In addition, a group of seven generic top-level domains (gTLD) was implemented which represented a set of categories of names and multi-organizations.[10] These were the domains gov, edu, com, mil, org, net, and int. These two types of top-level domains (TLDs) are the highest level of domain names of the Internet. Top-level domains form the DNS root zone of the hierarchical Domain Name System. Every domain name ends with a top-level domain label.

During the growth of the Internet, it became desirable to create additional generic top-level domains. As of October 2009, 21 generic top-level domains and 250 two-letter country-code top-level domains existed.[11] In addition, the ARPA domain serves technical purposes in the infrastructure of the Domain Name System.

During the 32nd International Public ICANN Meeting in Paris in 2008,[12] ICANN started a new process of TLD naming policy to take a "significant step forward on the introduction of new generic top-level domains." This program envisions the availability of many new or already proposed domains, as well as a new application and implementation process.[13] Observers believed that the new rules could result in hundreds of new top-level domains to be registered.[14] In 2012, the program commenced, and received 1930 applications.[15] By 2016, the milestone of 1000 live gTLD was reached.

The Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) maintains an annotated list of top-level domains in the DNS root zone database.[16]

For special purposes, such as network testing, documentation, and other applications, IANA also reserves a set of special-use domain names.[17] This list contains domain names such as example, local, localhost, and test. Other top-level domain names containing trade marks are registered for corporate use. Cases include brands such as BMW, Google, and Canon.[18]

Below the top-level domains in the domain name hierarchy are the second-level domain (SLD) names. These are the names directly to the left of .com, .net, and the other top-level domains. As an example, in the domain example.co.uk, co is the second-level domain.

Next are third-level domains, which are written immediately to the left of a second-level domain. There can be fourth- and fifth-level domains, and so on, with virtually no limitation. Each label is separated by a full stop (dot). An example of an operational domain name with four levels of domain labels is sos.state.oh.us. 'sos' is said to be a sub-domain of 'state.oh.us', and 'state' a sub-domain of 'oh.us', etc. In general, subdomains are domains subordinate to their parent domain. An example of very deep levels of subdomain ordering are the IPv6 reverse resolution DNS zones, e.g., 1.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.0.ip6.arpa, which is the reverse DNS resolution domain name for the IP address of a loopback interface, or the localhost name.

Second-level (or lower-level, depending on the established parent hierarchy) domain names are often created based on the name of a company (e.g., bbc.co.uk), product or service (e.g. hotmail.com). Below these levels, the next domain name component has been used to designate a particular host server. Therefore, ftp.example.com might be an FTP server, www.example.com would be a World Wide Web server, and mail.example.com could be an email server, each intended to perform only the implied function. Modern technology allows multiple physical servers with either different (cf. load balancing) or even identical addresses (cf. anycast) to serve a single hostname or domain name, or multiple domain names to be served by a single computer. The latter is very popular in Web hosting service centers, where service providers host the websites of many organizations on just a few servers.

The hierarchical DNS labels or components of domain names are separated in a fully qualified name by the full stop (dot, .).

The character set allowed in the Domain Name System is based on ASCII and does not allow the representation of names and words of many languages in their native scripts or alphabets. ICANN approved the Internationalized domain name (IDNA) system, which maps Unicode strings used in application user interfaces into the valid DNS character set by an encoding called Punycode. For example, københavn.eu is mapped to xn--kbenhavn-54a.eu. Many registries have adopted IDNA.

The first commercial Internet domain name, in the TLD com, was registered on 15 March 1985 in the name symbolics.com by Symbolics Inc., a computer systems firm in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

By 1992, fewer than 15,000 com domains had been registered.

In the first quarter of 2015, 294 million domain names had been registered.[19] A large fraction of them are in the com TLD, which as of December 21, 2014, had 115.6 million domain names,[20] including 11.9 million online business and e-commerce sites, 4.3 million entertainment sites, 3.1 million finance related sites, and 1.8 million sports sites.[21] As of July 15, 2012, the com TLD had more registrations than all of the ccTLDs combined.[22]

As of December 31, 2023,[update] 359.8 million domain names had been registered.[23]

The right to use a domain name is delegated by domain name registrars, which are accredited by the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), the organization charged with overseeing the name and number systems of the Internet. In addition to ICANN, each top-level domain (TLD) is maintained and serviced technically by an administrative organization operating a registry. A registry is responsible for maintaining the database of names registered within the TLD it administers. The registry receives registration information from each domain name registrar authorized to assign names in the corresponding TLD and publishes the information using a special service, the WHOIS protocol.

Registries and registrars usually charge an annual fee for the service of delegating a domain name to a user and providing a default set of name servers. Often, this transaction is termed a sale or lease of the domain name, and the registrant may sometimes be called an "owner", but no such legal relationship is actually associated with the transaction, only the exclusive right to use the domain name. More correctly, authorized users are known as "registrants" or as "domain holders".

ICANN publishes the complete list of TLD registries and domain name registrars. Registrant information associated with domain names is maintained in an online database accessible with the WHOIS protocol. For most of the 250 country code top-level domains (ccTLDs), the domain registries maintain the WHOIS (Registrant, name servers, expiration dates, etc.) information.

Some domain name registries, often called network information centers (NIC), also function as registrars to end-users. The major generic top-level domain registries, such as for the com, net, org, info domains and others, use a registry-registrar model consisting of hundreds of domain name registrars (see lists at ICANN[24] or VeriSign).[25] In this method of management, the registry only manages the domain name database and the relationship with the registrars. The registrants (users of a domain name) are customers of the registrar, in some cases through additional layers of resellers.

There are also a few other alternative DNS root providers that try to compete or complement ICANN's role of domain name administration, however, most of them failed to receive wide recognition, and thus domain names offered by those alternative roots cannot be used universally on most other internet-connecting machines without additional dedicated configurations.

In the process of registering a domain name and maintaining authority over the new name space created, registrars use several key pieces of information connected with a domain:

A domain name consists of one or more labels, each of which is formed from the set of ASCII letters, digits, and hyphens (a–z, A–Z, 0–9, -), but not starting or ending with a hyphen. The labels are case-insensitive; for example, 'label' is equivalent to 'Label' or 'LABEL'. In the textual representation of a domain name, the labels are separated by a full stop (period).

Domain names are often seen in analogy to real estate in that domain names are foundations on which a website can be built, and the highest quality domain names, like sought-after real estate, tend to carry significant value, usually due to their online brand-building potential, use in advertising, search engine optimization, and many other criteria.

A few companies have offered low-cost, below-cost or even free domain registration with a variety of models adopted to recoup the costs to the provider. These usually require that domains be hosted on their website within a framework or portal that includes advertising wrapped around the domain holder's content, revenue from which allows the provider to recoup the costs. Domain registrations were free of charge when the DNS was new. A domain holder may provide an infinite number of subdomains in their domain. For example, the owner of example.org could provide subdomains such as foo.example.org and foo.bar.example.org to interested parties.

Many desirable domain names are already assigned and users must search for other acceptable names, using Web-based search features, or WHOIS and dig operating system tools. Many registrars have implemented domain name suggestion tools which search domain name databases and suggest available alternative domain names related to keywords provided by the user.

The business of resale of registered domain names is known as the domain aftermarket. Various factors influence the perceived value or market value of a domain name. Most of the high-prize domain sales are carried out privately.[26] Also, it is called confidential domain acquiring or anonymous domain acquiring.[27]

Intercapping is often used to emphasize the meaning of a domain name, because DNS names are not case-sensitive. Some names may be misinterpreted in certain uses of capitalization. For example: Who Represents, a database of artists and agents, chose whorepresents.com,[28] which can be misread. In such situations, the proper meaning may be clarified by placement of hyphens when registering a domain name. For instance, Experts Exchange, a programmers' discussion site, used expertsexchange.com, but changed its domain name to experts-exchange.com.[29]

The domain name is a component of a uniform resource locator (URL) used to access websites, for example:

A domain name may point to multiple IP addresses to provide server redundancy for the services offered, a feature that is used to manage the traffic of large, popular websites.

Web hosting services, on the other hand, run servers that are typically assigned only one or a few addresses while serving websites for many domains, a technique referred to as virtual web hosting. Such IP address overloading requires that each request identifies the domain name being referenced, for instance by using the HTTP request header field Host:, or Server Name Indication.

Critics often claim abuse of administrative power over domain names. Particularly noteworthy was the VeriSign Site Finder system which redirected all unregistered .com and .net domains to a VeriSign webpage. For example, at a public meeting with VeriSign to air technical concerns about Site Finder,[30] numerous people, active in the IETF and other technical bodies, explained how they were surprised by VeriSign's changing the fundamental behavior of a major component of Internet infrastructure, not having obtained the customary consensus. Site Finder, at first, assumed every Internet query was for a website, and it monetized queries for incorrect domain names, taking the user to VeriSign's search site. Other applications, such as many implementations of email, treat a lack of response to a domain name query as an indication that the domain does not exist, and that the message can be treated as undeliverable. The original VeriSign implementation broke this assumption for mail, because it would always resolve an erroneous domain name to that of Site Finder. While VeriSign later changed Site Finder's behaviour with regard to email, there was still widespread protest about VeriSign's action being more in its financial interest than in the interest of the Internet infrastructure component for which VeriSign was the steward.

Despite widespread criticism, VeriSign only reluctantly removed it after the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) threatened to revoke its contract to administer the root name servers. ICANN published the extensive set of letters exchanged, committee reports, and ICANN decisions.[31]

There is also significant disquiet regarding the United States Government's political influence over ICANN. This was a significant issue in the attempt to create a .xxx top-level domain and sparked greater interest in alternative DNS roots that would be beyond the control of any single country.[32]

Additionally, there are numerous accusations of domain name front running, whereby registrars, when given whois queries, automatically register the domain name for themselves. Network Solutions has been accused of this.[33]

In the United States, the Truth in Domain Names Act of 2003, in combination with the PROTECT Act of 2003, forbids the use of a misleading domain name with the intention of attracting Internet users into visiting Internet pornography sites.

The Truth in Domain Names Act follows the more general Anticybersquatting Consumer Protection Act passed in 1999 aimed at preventing typosquatting and deceptive use of names and trademarks in domain names.

In the early 21st century, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) pursued the seizure of domain names, based on the legal theory that domain names constitute property used to engage in criminal activity, and thus are subject to forfeiture. For example, in the seizure of the domain name of a gambling website, the DOJ referenced and .[34][1] In 2013 the US government seized Liberty Reserve, citing .[35]

The U.S. Congress passed the Combating Online Infringement and Counterfeits Act in 2010. Consumer Electronics Association vice president Michael Petricone was worried that seizure was a blunt instrument that could harm legitimate businesses.[36][37] After a joint operation on February 15, 2011, the DOJ and the Department of Homeland Security claimed to have seized ten domains of websites involved in advertising and distributing child pornography, but also mistakenly seized the domain name of a large DNS provider, temporarily replacing 84,000 websites with seizure notices.[38]

In the United Kingdom, the Police Intellectual Property Crime Unit (PIPCU) has been attempting to seize domain names from registrars without court orders.[39]

PIPCU and other UK law enforcement organisations make domain suspension requests to Nominet which they process on the basis of breach of terms and conditions. Around 16,000 domains are suspended annually, and about 80% of the requests originate from PIPCU.[40]

Because of the economic value it represents, the European Court of Human Rights has ruled that the exclusive right to a domain name is protected as property under article 1 of Protocol 1 to the European Convention on Human Rights.[41]

ICANN Business Constituency (BC) has spent decades trying to make IDN variants work at the second level, and in the last several years at the top level. Domain name variants are domain names recognized in different character encodings, like a single domain presented in traditional Chinese and simplified Chinese. It is an Internationalization and localization problem. Under Domain Name Variants, the different encodings of the domain name (in simplified and traditional Chinese) would resolve to the same host.[42][43]

According to John Levine, an expert on Internet related topics, "Unfortunately, variants don't work. The problem isn't putting them in the DNS, it's that once they're in the DNS, they don't work anywhere else."[42]

A fictitious domain name is a domain name used in a work of fiction or popular culture to refer to a domain that does not actually exist, often with invalid or unofficial top-level domains such as ".web", a usage exactly analogous to the dummy 555 telephone number prefix used in film and other media. The canonical fictitious domain name is "example.com", specifically set aside by IANA in RFC 2606 for such use, along with the .example TLD.

Domain names used in works of fiction have often been registered in the DNS, either by their creators or by cybersquatters attempting to profit from it. This phenomenon prompted NBC to purchase the domain name Hornymanatee.com after talk-show host Conan O'Brien spoke the name while ad-libbing on his show. O'Brien subsequently created a website based on the concept and used it as a running gag on the show.[44] Companies whose works have used fictitious domain names have also employed firms such as MarkMonitor to park fictional domain names in order to prevent misuse by third parties.[45]

Misspelled domain names, also known as typosquatting or URL hijacking, are domain names that are intentionally or unintentionally misspelled versions of popular or well-known domain names. The goal of misspelled domain names is to capitalize on internet users who accidentally type in a misspelled domain name, and are then redirected to a different website.

Misspelled domain names are often used for malicious purposes, such as phishing scams or distributing malware. In some cases, the owners of misspelled domain names may also attempt to sell the domain names to the owners of the legitimate domain names, or to individuals or organizations who are interested in capitalizing on the traffic generated by internet users who accidentally type in the misspelled domain names.

To avoid being caught by a misspelled domain name, internet users should be careful to type in domain names correctly, and should avoid clicking on links that appear suspicious or unfamiliar. Additionally, individuals and organizations who own popular or well-known domain names should consider registering common misspellings of their domain names in order to prevent others from using them for malicious purposes.

The term Domain name spoofing (or simply though less accurately, Domain spoofing) is used generically to describe one or more of a class of phishing attacks that depend on falsifying or misrepresenting an internet domain name.[46][47] These are designed to persuade unsuspecting users into visiting a web site other than that intended, or opening an email that is not in reality from the address shown (or apparently shown).[48] Although website and email spoofing attacks are more widely known, any service that relies on domain name resolution may be compromised.

There are a number of better-known types of domain spoofing:

Parramatta (/ËŒpærəˈmætÉ™/; Dharuk: Burramatta) is a suburb and major commercial centre in Greater Western Sydney.[7][8] Parramatta is located approximately 24 kilometres (15 mi) west of the Sydney CBD, on the banks of the Parramatta River.[2] It is commonly regarded as the secondary central business district of metropolitan Sydney.

Parramatta is the municipal seat of the local government area of the City of Parramatta and is often regarded as one of the primary centres of the Greater Sydney metropolitan region, along with the Sydney CBD, Penrith, Campbelltown, and Liverpool.[9] Parramatta also has a long history as a second administrative centre in the Sydney metropolitan region, playing host to a number of government departments,[10] as well as state and federal courts. It is often colloquially referred to as "Parra".

Parramatta, which was founded as a British settlement in 1788, the same year as Sydney, is the oldest inland European settlement in Australia and serves as the economic centre of Greater Western Sydney.[11] Since 2000, state government agencies such as the New South Wales Police Force and Sydney Water[12] have relocated to Parramatta from Central Sydney. The 151st meridian east runs directly through the suburb.

Radiocarbon dating suggests human activity occurred in Parramatta from around 30,000 years ago.[13] The Darug people who lived in the area before European settlement regarded the area as rich in food from the river and forests. They named the area Baramada or Burramatta ('Parramatta') which means Eel ("Burra") Place ("matta"), with the resident Indigenous people being called the Burramattagal. Similar Darug words include Cabramatta (Grub place) and Wianamatta (Mother place).[14] Other references[which?] are derived from the words of Captain Watkin Tench, a white British man with a poor understanding of the Darug language, and are incorrect.[citation needed] To this day many eels and other sea creatures are attracted to nutrients that are concentrated where the saltwater of Port Jackson meets the freshwater of the Parramatta River. The Parramatta Eels rugby league club chose their symbol as a result of this phenomenon.

Parramatta was colonised by the British in 1788, the same year as Sydney. As such, Parramatta is the second oldest city in Australia, being only 10 months younger than Sydney. The British colonists, who had arrived in January 1788 on the First Fleet at Sydney Cove, had only enough food to support themselves for a short time and the soil around Sydney Cove proved too poor to grow the amount of food that 1,000 convicts, soldiers and administrators needed to survive. During 1788, Governor Arthur Phillip had reconnoitred several places before choosing Parramatta as the most likely place for a successful large farm.[15] Parramatta was the furthest navigable point inland on the Parramatta River (i.e. furthest from the thin, sandy coastal soil) and also the point at which the river became freshwater and therefore useful for farming.

On Sunday 2 November 1788, Governor Phillip took a detachment of marines along with a surveyor and, in boats, made his way upriver to a location that he called The Crescent, a defensible hill curved round a river bend, now in Parramatta Park. The Burramattagal were rapidly displaced with notable residents Maugoran, Boorong and Baludarri being forced from their lands.[16]

As a settlement developed, Governor Phillip gave it the name "Rose Hill" after British politician George Rose.[17] On 4 June 1791 Phillip changed the name of the township to Parramatta, approximating the term used by the local Aboriginal people.[18] A neighbouring suburb acquired the name "Rose Hill", which today is spelt "Rosehill".

In an attempt to deal with the food crisis, Phillip in 1789 granted a convict named James Ruse the land of Experiment Farm at Parramatta on the condition that he develop a viable agriculture. There, Ruse became the first European to successfully grow grain in Australia. The Parramatta area was also the site of the pioneering of the Australian wool industry by John Macarthur's Elizabeth Farm in the 1790s. Philip Gidley King's account of his visit to Parramatta on 9 April 1790 is one of the earliest descriptions of the area. Walking four miles with Governor Phillip to Prospect, he saw undulating grassland interspersed with magnificent trees and a great number of kangaroos and emus.[19]

The Battle of Parramatta, a major battle of the Australian frontier wars, occurred in March 1797 where Eora leader Pemulwuy led a group of Bidjigal warriors, estimated to be at least 100, in an attack on the town of Parramatta. The local garrison withdrew to their barracks and Pemulwuy held the town until he was eventually shot and wounded. A year later, a government farm at Toongabbie was attacked by Pemulwuy, who challenged the New South Wales Corps to a fight.[20][21]

Governor Arthur Phillip built a small house for himself on the hill of The Crescent. In 1799 this was replaced by a larger residence which, substantially improved by Governor Lachlan Macquarie from 1815 to 1818, has survived to the present day, making it the oldest surviving Government House anywhere in Australia. It was used as a retreat by Governors until the 1850s, with one Governor (Governor Brisbane) making it his principal home for a short period in the 1820s.

In 1803, another famous incident occurred in Parramatta, involving a convicted criminal named Joseph Samuel, originally from England. Samuel was convicted of murder and sentenced to death by hanging, but the rope broke. In the second attempt, the noose slipped off his neck. In the third attempt, the new rope broke. Governor King was summoned and pardoned Samuel, as the incident appeared to him to be divine intervention.[22]

In 1814, Macquarie opened a school for Aboriginal children at Parramatta as part of a policy of improving relations between Aboriginal and European communities. This school was later relocated to "Black Town".[23]

Parramatta was gazetted as a city on 19 November 1976, and later, a suburb on 10 June 1994.

The first significant skyscrapers began to emerge in Parramatta in the late 1990s and the suburb transformed into a major business and residential hub in the early 2000s. Since then, the suburb's growth has accelerated in the past decade.

On 20 December 2024, the first stage of the Parramatta Light Rail was completed.

Parramatta has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification: Cfa) with mild to cool, somewhat short winters and warm to usually hot summers, alongside moderate rainfall spread throughout the year.

Summer maximum temperatures are quite variable, often reaching above 35 °C (95 °F), on average 13.1 days in the summer season, and sometimes remaining in the low 20s, especially after a cold front or a sea breeze, such as the southerly buster. Northwesterlies can occasionally bring hot winds from the desert that can raise temperatures higher than 40 °C (104 °F) mostly from November to February, and sometimes above 44 °C (111 °F) in January severe heatwaves. The record highest temperature (since 1967) was 47.0 °C (116.6 °F) on 4 January 2020. Parramatta is warmer than Sydney CBD in the summer due to the urban heat island effect and its inland location. In extreme cases though, it can be 5–10 °C (9–18 °F) warmer than Sydney, especially when sea breezes do not penetrate inland on hot summer and spring days. For example, on 28 November 2009, the city reached 29.3 °C (84.7 °F),[24] while Parramatta reached 39.0 °C (102.2 °F),[25] almost 10 °C (18 °F) higher. In the summer, Parramatta, among other places in western Sydney, can often be the hottest place in the world because of the Blue Mountains trapping hot air in the region, in addition to the UHI effect.[26]

Rainfall is slightly higher during the first three months of the year because the anticlockwise-rotating subtropical high is to the south of the country, thereby allowing moist easterlies from the Tasman Sea to penetrate the city.[27][28] The second half of the year tends to be drier (late winter/spring) since the subtropical high is to the north of the city, thus permitting dry westerlies from the interior to dominate.[29] Drier winters are also owed to its position on the leeward side of the Great Dividing Range, which block westerly cold fronts (that are more common in late winter) and thus would become foehn winds, whereby allowing decent amount of sunny days and relatively low precipitation in that period.[30] Thunderstorms are common in the months from early spring to early autumn, occasionally quite severe thunderstorms can occur. Snow is virtually unknown, having been recorded only in 1836 and 1896[31] Parrammatta gets 106.6 days of clear skies annually.

Depending on the wind direction, summer weather may be humid or dry, though the humidity is mostly in the comfortable range, with the late summer/autumn period having a higher average humidity than late winter/early spring.

| Climate data for Parramatta North (1991–2020 averages, 1967–present extremes) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 47.0 (116.6) |

44.5 (112.1) |

40.5 (104.9) |

37.0 (98.6) |

29.2 (84.6) |

25.5 (77.9) |

26.8 (80.2) |

30.6 (87.1) |

36.5 (97.7) |

40.1 (104.2) |

42.7 (108.9) |

44.0 (111.2) |

47.0 (116.6) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 40.1 (104.2) |

37.5 (99.5) |

33.9 (93.0) |

30.3 (86.5) |

26.2 (79.2) |

22.3 (72.1) |

22.7 (72.9) |

25.7 (78.3) |

30.8 (87.4) |

34.3 (93.7) |

36.6 (97.9) |

37.6 (99.7) |

41.6 (106.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 29.1 (84.4) |

28.3 (82.9) |

26.5 (79.7) |

23.9 (75.0) |

20.9 (69.6) |

18.2 (64.8) |

17.8 (64.0) |

19.5 (67.1) |

22.3 (72.1) |

24.5 (76.1) |

25.8 (78.4) |

27.7 (81.9) |

23.7 (74.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 17.9 (64.2) |

17.7 (63.9) |

15.9 (60.6) |

12.6 (54.7) |

9.6 (49.3) |

7.5 (45.5) |

6.3 (43.3) |

6.9 (44.4) |

9.4 (48.9) |

12.0 (53.6) |

14.3 (57.7) |

16.4 (61.5) |

12.2 (54.0) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | 12.9 (55.2) |

12.7 (54.9) |

10.9 (51.6) |

7.8 (46.0) |

4.5 (40.1) |

2.9 (37.2) |

1.7 (35.1) |

2.4 (36.3) |

4.5 (40.1) |

6.5 (43.7) |

8.6 (47.5) |

10.9 (51.6) |

1.2 (34.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 10.1 (50.2) |

9.2 (48.6) |

6.8 (44.2) |

4.0 (39.2) |

1.4 (34.5) |

0.8 (33.4) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

0.7 (33.3) |

0.7 (33.3) |

3.6 (38.5) |

4.0 (39.2) |

7.7 (45.9) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 89.9 (3.54) |

130.3 (5.13) |

99.1 (3.90) |

78.3 (3.08) |

61.3 (2.41) |

99.0 (3.90) |

48.0 (1.89) |

47.4 (1.87) |

48.5 (1.91) |

61.3 (2.41) |

82.0 (3.23) |

78.5 (3.09) |

923.6 (36.36) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 8.6 | 9.0 | 9.9 | 7.0 | 6.3 | 7.9 | 6.0 | 4.8 | 5.7 | 7.0 | 8.7 | 8.3 | 89.2 |

| Average afternoon relative humidity (%) | 56 | 59 | 58 | 56 | 59 | 58 | 55 | 45 | 46 | 50 | 54 | 55 | 54 |

| Average dew point °C (°F) | 16.2 (61.2) |

16.8 (62.2) |

15.5 (59.9) |

12.7 (54.9) |

9.9 (49.8) |

7.6 (45.7) |

5.6 (42.1) |

5.5 (41.9) |

7.7 (45.9) |

9.9 (49.8) |

12.3 (54.1) |

14.3 (57.7) |

11.2 (52.2) |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology[32] | |||||||||||||

Church Street is home to many shops and restaurants. The northern end of Church Street, close to Lennox Bridge, features al fresco dining with a diverse range of cuisines. Immediately south of the CBD Church Street is known across Sydney as 'Auto Alley' for the many car dealerships lining both sides of the street as far as the M4 Motorway.[33]

Since 2000, Parramatta has seen the consolidation of its role as a government centre, with the relocation of agencies such as the New South Wales Police Force Headquarters and the Sydney Water Corporation[12] from Sydney CBD. At the same time, major construction work occurred around the railway station with the expansion of Westfield Shoppingtown and the creation of a new transport interchange. The western part of the Parramatta CBD is known as the Parramatta Justice Precinct and houses the corporate headquarters of the Department of Communities and Justice. Other legal offices include the Children's Court of New South Wales and the Sydney West Trial Courts, Legal Aid Commission of NSW, Office of Trustee and Guardian (formerly the Office of the Protective Commissioner), NSW Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, and the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions. Nearby on Marsden Street is the Parramatta Courthouse and the Drug Court of New South Wales. The Garfield Barwick Commonwealth Law Courts Building (named in honour of Sir Garfield Barwick), houses courts of the Federal Magistrates Court and the Family Court of Australia. The NSW Government has also announced plans to secure up to 45,000 m2 of new A-grade leased office space in Parramatta to relocate a further 4,000 workers from the Sydney CBD.[34]

Parramatta Square (previously known as Civic Place) is a civic precinct located in the heart of the city, adjacent to Parramatta Town Hall. The Parramatta Square construction works included a redevelopment of the Parramatta Civic Centre, construction of a new culture and arts centre, and the construction of a new plaza. The designs of the first two projects, a 65-storey residential skyscraper and an office building were announced on 20 July 2012.[35] Concerns from CASA about infringements into controlled airspace from the height of the residential tower resulted in 8 Parramatta Square being turned into a 55-story commercial building, rather than the originally proposed 65-storey residential tower.[36] Parramatta Square became home to 3,000 National Australia Bank employees, relocated from the Sydney CBD.[37] Other notable commercial tenants who have established a presence at Parramatta Square include Westpac, Endeavour Energy, KPMG and Deloitte.[38]

Centenary Square, formerly known as Centenary Plaza, was created in 1975 when the then Parramatta City Council closed a section of the main street to traffic to create a pedestrian plaza. It features an 1888 Centennial Memorial Fountain and adjoins the 1883 Parramatta Town Hall and St John's Cathedral.[39]

A hospital known as The Colonial Hospital was established in Parramatta in 1818.[40] This then became Parramatta District Hospital. Jeffery House was built in the 1940s. With the construction of the nearby Westmead Hospital complex public hospital services in Parramatta were reduced but after refurbishment Jeffery House again provides clinical health services. Nearby, Brislington House has had a long history with health services. It is the oldest colonial building in Parramatta, dating to 1821.[41] It became a doctors residence before being incorporated into the Parramatta Hospital in 1949.

Parramatta is a major business and commercial centre, and home to Westfield Parramatta, the tenth largest shopping centre in Australia.[42] Parramatta is also the major transport hub for Western Sydney, servicing trains and buses, as well as having a ferry wharf and future light rail and metro services. Major upgrades have occurred around Parramatta railway station with the creation of a new transport interchange, and the ongoing development of the Parramatta Square local government precinct.[43]

Church Street takes its name from St John's Cathedral (Anglican), which was built in 1802 and is the oldest church in Parramatta. While the present building is not the first on the site, the towers were built during the time of Governor Macquarie, and were based on those of the church at Reculver, England, at the suggestion of his wife, Elizabeth.[44] The historic St John's Cemetery is located nearby on O'Connell Street.[45]

St Patrick's Cathedral (Roman Catholic) is one of the oldest Catholic churches in Australia. Construction commenced in 1836, but it wasn't officially complete until 1837. In 1854 a new church was commissioned, although the tower was not completed until 1880, with the spire following in 1883.[46] It was built on the site to meet the needs of a growing congregation. It was destroyed by fire in 1996, with only the stone walls remaining.

On 29 November 2003, the new St Patrick's Cathedral was dedicated.[47] The historic St Patrick's Cemetery is located in North Parramatta. The Uniting Church is represented by Leigh Memorial Church.[48] Parramatta Salvation Army is one of the oldest active Salvation Army Corps in Australia. Parramatta is also home to the Parramatta and Districts Synagogue, which services the Jewish community of western Sydney.[49]

The Greek Orthodox Parish and Community of St Ioannis (St John The Frontrunner) Greek Orthodox Church was established in Parramatta in May 1960 under the ecumenical jurisdiction of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia to serve the predominantly emigrating Greek population of Greater Western Sydney. Originally, the liturgies were held in the hall of St John's Ambulance Brigade in Harris Park until the completion of the church in December 1966 located in Hassall Street Parramatta. The parish sold this property in 2014 and is now located at the corner of George and Purchase Streets.[50] The Parish Community of St Ioannis continues to serve over 5,000 Greek parishioners.[51]

A Buddhist temple is located in Cowper Street, Parramatta.[52] Parramatta's Mosque is in an apartment building on Marsden Street, Parramatta.[53] The district is served by BAPS Swaminarayan Hindu temple located on Eleanor St, Rosehill,[54] and a Murugan Hindu temple in Mays Hill, off Great Western Highway.[55]

Parramatta Park is a large park adjacent to Western Sydney Stadium that is a popular venue for walking, jogging and bike riding. It was formerly the Governor's Domain, being land set aside for the Governor to supply his farming needs, until it was gazetted as a public park in 1858.[56] As the Governor's Domain, the grounds were considerably larger than the current 85 hectare Parramatta Park, extending from Parramatta Road in the south as evident by a small gatehouse adjacent to Parramatta High School. For a time Parramatta Park housed a zoo[57] until 1951 when the animals were transferred to Taronga Zoo.

Parramatta is known as the 'River City' as the Parramatta River flows through the Parramatta CBD.[58] Its foreshore features a playground, seating, picnic tables and pathways that are increasingly popular with residents, visitors and CBD workers.[59]

Prince Alfred Square is a Victorian era park located within the CBD on the northern side of the Parramatta River. It is one of the oldest public parks in New South Wales with trees dating from c. 1869. Prior to being a public park, it was the site of Parramatta's second gaol from 1804 until 1841 and the first female factory in Australia between 1804 and 1821.

In contrast to the high level of car dependency throughout Sydney, a greater proportion of Parramatta's workers travelled to work on public transport (45.2%) than by car (36.2%) in 2016.[60]

Parramatta railway station is served by Sydney Trains' Cumberland Line, Leppington & Inner West Line and North Shore & Western Line services.[61] NSW TrainLink operates intercity services on the Blue Mountains Line as well as services to rural New South Wales. The station was originally opened in 1855, located in what is now Granville, and known as Parramatta Junction. The station was moved to its current location and opened on 4 July 1860, five years after the first railway line in Sydney was opened, running from Sydney to Parramatta Junction.[62] It was upgraded in the 2000s, with work beginning in late 2003 and the new interchange opening on 19 February 2006.[63]

The light rail Westmead & Carlingford Line runs from Westmead to Carlingford via the Parramatta city centre. A future branch will run to Sydney Olympic Park.[64]

The under construction Sydney Metro West will be a metro line run between the Sydney central business district and Westmead. Announced in 2016,[65] the line is set to open in 2032 with a station in Parramatta.[66]

Parramatta is also serviced by a major bus interchange located on the south eastern side of the railway station. The interchange is served by buses utilising the North-West T-way to Rouse Hill and the Liverpool–Parramatta T-way to Liverpool. Parramatta is also serviced by one high frequency Metrobus service:

A free bus Route 900 is operated by Transit Systems in conjunction with the state government. Route 900 circles Parramatta CBD.[67] A free bus also links Western Sydney Stadium to Parramatta railway station during major sporting events.

The Parramatta ferry wharf is at the Charles Street Weir, which divides the tidal saltwater from the freshwater of the upper river, on the eastern boundary of the Central Business District. The wharf is the westernmost destination of Sydney Ferries' Parramatta River ferry services.[68]

Parramatta Road has always been an important thoroughfare for Sydney from its earliest days. From Parramatta the major western road for the state is the Great Western Highway. The M4 Western Motorway, running parallel to the Great Western Highway has taken much of the traffic away from these roads, with entrance and exit ramps close to Parramatta.

James Ruse Drive serves as a partial ring-road circling around the eastern part of Parramatta to join with the Cumberland Highway to the north west of the city.

The main north-south route through Parramatta is Church Street. To the north it becomes Windsor Road, and to the south it becomes Woodville Road.

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 17,982 | — |

| 2006 | 18,448 | +2.6% |

| 2011 | 19,745 | +7.0% |

| 2016 | 25,798 | +30.7% |

| 2021 | 30,211 | +17.1% |

According to the 2016 census conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the suburb of Parramatta had a population of 30,211. Of these:[69]

Parramatta is home to several primary and secondary schools. Arthur Phillip High School was established in 1960 in its own right, in buildings which had been used continuously as a school since 1875 is the oldest continuously operating public school in Parramatta. Parramatta High School was the first coeducational school in the Sydney metropolitan area established in 1913. Our Lady of Mercy College is one of the oldest Catholic schools in Australia. Macarthur Girls High School is successor to an earlier school 'Parramatta Commercial and Household Arts School'. Others schools include Parramatta Public School, Parramatta East Public School, Parramatta West Public School, and St Patrick's Primary Parramatta.

Several tertiary education facilities are also located within Parramatta. A University of New England study centre and two Western Sydney University campuses are situated in Parramatta. The Western Sydney University Parramatta Campus consists of two sites: Parramatta South (the primary site) which occupies the site of the historic Female Orphan School[72] and Parramatta North (the secondary site) which includes the adjacent Western Sydney University Village Parramatta (formerly UWS Village Parramatta) an on campus student village accommodation. Whereby, the flagship Parramatta City Campus Precinct consists of two buildings: the Engineering Innovation Hub located at 6 Hassall Street and the Peter Shergold Building located at 1 Parramatta Square (169 Macquarie Street).[73] Alphacrucis University College is a Christian liberal arts college with a campus in Parramatta located at 30 Cowper Street.[74] The University of Sydney has also announced that it intends to establish a new campus in Parramatta.[75]

The Parramatta Advertiser is the local newspaper serving Parramatta and surrounding suburbs.

On 16 March 2020, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation opened a new Western Sydney newsroom in Horwood Place at Parramatta incorporating space for 12 staff and news production equipment with the capacity to broadcast live radio programs.[76] According to the ABC, the opening formed part of its strategic goal to improve its presence in outer metropolitan areas.[76] Additionally, the ABC announced on 16 June 2021 its intention to relocate approximately 300 employees to Parramatta, which is part of a five-year plan which aims to have 75% of its content makers based away from the network's Ultimo headquarters by 2025.[77][78]

As the centre of the City of Parramatta, as well as the centre and second largest business district of Sydney, Parramatta hosts many festivals and events.[79] Riverside Theatres is a performing arts centre located on the northern bank of Parramatta River. The city hosts the following events:

Parramatta Park contains Old Government House and thus Parramatta was once the capital of the colony of New South Wales until Governors returned to residing in Sydney in 1846.[83] Another feature is the natural amphitheatre located on one of the bends of the river, named by Governor Philip as "the Crescent", which is used to stage concerts. It is home to the Dairy Cottage, built from 1798 to 1805, originally a single-room cottage and is one of the earliest surviving cottages in Australia.

The remains of Governor Brisbane's private astronomical observatory, constructed in 1822, are visible. Astronomers who worked at the observatory, discovering thousands of new stars and deep sky objects, include James Dunlop and Carl Rümker. In 1822, the architect S. L. Harris designed the Bath House for Governor Brisbane and built it in 1823. Water was pumped to the building through lead pipes from the river. In 1886, it was converted into a pavilion.[84]

Parramatta is the home of several professional sports teams. These teams include the Parramatta Eels of the National Rugby League and Western Sydney Wanderers of the A-League. Both teams formerly played matches at Parramatta Stadium that has since been demolished, and replaced with the 30,000-seat Western Sydney Stadium.[86] Parramatta Stadium was also home to the now dissolved Sydney Wave of the former Australian Baseball League and Parramatta Power of the former National Soccer League. The newly built Bankwest Stadium opened its gates for the community on 14 April 2019 with free entry for all fans. Located on O’Connell Street, the stadium is in proximity of the Parramatta CBD. The opening sporting event was the 2019 Round 6 NRL clash between Western Sydney rivals the Parramatta Eels and Wests Tigers on Easter Monday 22 April. The Eels won the match by a score of 51–6. It is being predicted that the new stadium will boost Western Sydney economy by contributing millions of dollars to it.[87]

Duran Duran's “Union of the Snake” music video with Russell Mulcahy was filmed in 1983 at Parramatta using 35mm film.[88]

The 2013 superhero film The Wolverine used the intersection of George Street and Smith Street as a filming location to depict Tokyo, Japan.[89]

Parramatta has a number of heritage-listed sites, including:

|

|

This article's "criticism" or "controversy" section may compromise the article's neutrality. (June 2024)

|

|

|

Screenshot of Google Maps in a web browser

|

|

|

Type of site

|

Web mapping |

|---|---|

| Available in | 74 languages |

|

List of languages

Afrikaans, Azerbaijani, Indonesian, Malay, Bosnian, Catalan, Czech, Danish, German (Germany), Estonian, English (United States), Spanish (Spain), Spanish (Latin America), Basque, Filipino, French (France), Galician, Croatian, Zulu, Icelandic, Italian, Swahili, Latvian, Lithuanian, Hungarian, Dutch, Norwegian, Uzbek, Polish, Portuguese (Brazil), Portuguese (Portugal), Romanian, Albanian, Slovak, Slovenian, Finnish, Swedish, Vietnamese, Turkish, Greek, Bulgarian, Kyrgyz, Kazakh, Macedonian, Mongolian, Russian, Serbian, Ukrainian, Georgian, Armenian, Hebrew, Urdu, Arabic, Persian, Amharic, Nepali, Hindi, Marathi, Bengali, Punjabi, Gujarati, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, Sinhala, Thai, Lao, Burmese, Khmer, Korean, Japanese, Simplified Chinese, Traditional Chinese

|

|

| Owner | |

| URL | google |

| Commercial | Yes |

| Registration | Optional, included with a Google Account |

| Launched | February 8, 2005 |

| Current status | Active |

| Written in | C++ (back-end), JavaScript, XML, Ajax (UI) |

Google Maps is a web mapping platform and consumer application offered by Google. It offers satellite imagery, aerial photography, street maps, 360° interactive panoramic views of streets (Street View), real-time traffic conditions, and route planning for traveling by foot, car, bike, air (in beta) and public transportation. As of 2020[update], Google Maps was being used by over one billion people every month around the world.[1]

Google Maps began as a C++ desktop program developed by brothers Lars and Jens Rasmussen in Australia at Where 2 Technologies. In October 2004, the company was acquired by Google, which converted it into a web application. After additional acquisitions of a geospatial data visualization company and a real-time traffic analyzer, Google Maps was launched in February 2005.[2] The service's front end utilizes JavaScript, XML, and Ajax. Google Maps offers an API that allows maps to be embedded on third-party websites,[3] and offers a locator for businesses and other organizations in numerous countries around the world. Google Map Maker allowed users to collaboratively expand and update the service's mapping worldwide but was discontinued from March 2017. However, crowdsourced contributions to Google Maps were not discontinued as the company announced those features would be transferred to the Google Local Guides program,[4] although users that are not Local Guides can still contribute.

Google Maps' satellite view is a "top-down" or bird's-eye view; most of the high-resolution imagery of cities is aerial photography taken from aircraft flying at 800 to 1,500 feet (240 to 460 m), while most other imagery is from satellites.[5] Much of the available satellite imagery is no more than three years old and is updated on a regular basis, according to a 2011 report.[6] Google Maps previously used a variant of the Mercator projection, and therefore could not accurately show areas around the poles.[7] In August 2018, the desktop version of Google Maps was updated to show a 3D globe. It is still possible to switch back to the 2D map in the settings.

Google Maps for mobile devices was first released in 2006; the latest versions feature GPS turn-by-turn navigation along with dedicated parking assistance features. By 2013, it was found to be the world's most popular smartphone app, with over 54% of global smartphone owners using it.[8] In 2017, the app was reported to have two billion users on Android, along with several other Google services including YouTube, Chrome, Gmail, Search, and Google Play.

Google Maps first started as a C++ program designed by two Danish brothers, Lars and Jens Eilstrup Rasmussen, and Noel Gordon and Stephen Ma, at the Sydney-based company Where 2 Technologies, which was founded in early 2003. The program was initially designed to be separately downloaded by users, but the company later pitched the idea for a purely Web-based product to Google management, changing the method of distribution.[9] In October 2004, the company was acquired by Google Inc.[10] where it transformed into the web application Google Maps. The Rasmussen brothers, Gordon and Ma joined Google at that time.

In the same month, Google acquired Keyhole, a geospatial data visualization company (with investment from the CIA), whose marquee application suite, Earth Viewer, emerged as the Google Earth application in 2005 while other aspects of its core technology were integrated into Google Maps.[11] In September 2004, Google acquired ZipDash, a company that provided real-time traffic analysis.[12]

The launch of Google Maps was first announced on the Google Blog on February 8, 2005.[13]

In September 2005, in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, Google Maps quickly updated its satellite imagery of New Orleans to allow users to view the extent of the flooding in various parts of that city.[14][15]

As of 2007, Google Maps was equipped with a miniature view with a draggable rectangle that denotes the area shown in the main viewport, and "Info windows" for previewing details about locations on maps.[16] As of 2024, this feature had been removed (likely several years prior).

On November 28, 2007, Google Maps for Mobile 2.0 was released.[17][18][19] It featured a beta version of a "My Location" feature, which uses the GPS / Assisted GPS location of the mobile device, if available, supplemented by determining the nearest wireless networks and cell sites.[18][19] The software looks up the location of the cell site using a database of known wireless networks and sites.[20][21] By triangulating the different signal strengths from cell transmitters and then using their location property (retrieved from the database), My Location determines the user's current location.[22]

On September 23, 2008, coinciding with the announcement of the first commercial Android device, Google announced that a Google Maps app had been released for its Android operating system.[23][24]

In October 2009, Google replaced Tele Atlas as their primary supplier of geospatial data in the US version of Maps and used their own data.[25]

On April 19, 2011, Map Maker was added to the American version of Google Maps, allowing any viewer to edit and add changes to Google Maps. This provides Google with local map updates almost in real-time instead of waiting for digital map data companies to release more infrequent updates.

On January 31, 2012, Google, due to offering its Maps for free, was found guilty of abusing the dominant position of its Google Maps application and ordered by a court to pay a fine and damages to Bottin Cartographer, a French mapping company.[26] This ruling was overturned on appeal.[27]

In June 2012, Google started mapping the UK's rivers and canals in partnership with the Canal and River Trust. The company has stated that "it would update the program during the year to allow users to plan trips which include locks, bridges and towpaths along the 2,000 miles of river paths in the UK."[28]

In December 2012, the Google Maps application was separately made available in the App Store, after Apple removed it from its default installation of the mobile operating system version iOS 6 in September 2012.[29]

On January 29, 2013, Google Maps was updated to include a map of North Korea.[30] As of May 3, 2013[update], Google Maps recognizes Palestine as a country, instead of redirecting to the Palestinian territories.[31]

In August 2013, Google Maps removed the Wikipedia Layer, which provided links to Wikipedia content about locations shown in Google Maps using Wikipedia geocodes.[32]

On April 12, 2014, Google Maps was updated to reflect the annexation of Ukrainian Crimea by Russia. Crimea is shown as the Republic of Crimea in Russia and as the Autonomous Republic of Crimea in Ukraine. All other versions show a dotted disputed border.[33]

In April 2015, on a map near the Pakistani city of Rawalpindi, the imagery of the Android logo urinating on the Apple logo was added via Map Maker and appeared on Google Maps. The vandalism was soon removed and Google publicly apologized.[34] However, as a result, Google disabled user moderation on Map Maker, and on May 12, disabled editing worldwide until it could devise a new policy for approving edits and avoiding vandalism.[35]

On April 29, 2015, users of the classic Google Maps were forwarded to the new Google Maps with the option to be removed from the interface.[36]

On July 14, 2015, the Chinese name for Scarborough Shoal was removed after a petition from the Philippines was posted on Change.org.[37]

On June 27, 2016, Google rolled out new satellite imagery worldwide sourced from Landsat 8, comprising over 700 trillion pixels of new data.[38] In September 2016, Google Maps acquired mapping analytics startup Urban Engines.[39]

In 2016, the Government of South Korea offered Google conditional access to the country's geographic database – access that already allows indigenous Korean mapping providers high-detail maps. Google declined the offer, as it was unwilling to accept restrictions on reducing the quality around locations the South Korean Government felt were sensitive (see restrictions on geographic data in South Korea).[40]

On October 16, 2017, Google Maps was updated with accessible imagery of several planets and moons such as Titan, Mercury, and Venus, as well as direct access to imagery of the Moon and Mars.[41][42]

In May 2018, Google announced major changes to the API structure starting June 11, 2018. This change consolidated the 18 different endpoints into three services and merged the basic and premium plans into one pay-as-you-go plan.[43] This meant a 1400% price raise for users on the basic plan, with only six weeks of notice. This caused a harsh reaction within the developers community.[44] In June, Google postponed the change date to July 16, 2018.

In August 2018, Google Maps designed its overall view (when zoomed out completely) into a 3D globe dropping the Mercator projection that projected the planet onto a flat surface.[45]

In January 2019, Google Maps added speed trap and speed camera alerts as reported by other users.[46][47]

On October 17, 2019, Google Maps was updated to include incident reporting, resembling a functionality in Waze which was acquired by Google in 2013.[48]

In December 2019, Incognito mode was added, allowing users to enter destinations without saving entries to their Google accounts.[49]

In February 2020, Maps received a 15th anniversary redesign.[50] It notably added a brand-new app icon, which now resembles the original icon in 2005.

On September 23, 2020, Google announced a COVID-19 Layer update for Google maps, which is designed to offer a seven-day average data of the total COVID-19-positive cases per 100,000 people in the area selected on the map. It also features a label indicating the rise and fall in the number of cases.[51]

In January 2021, Google announced that it would be launching a new feature displaying COVID-19 vaccination sites.[52]

In January 2021, Google announced updates to the route planner that would accommodate drivers of electric vehicles. Routing would take into account the type of vehicle, vehicle status including current charge, and the locations of charging stations.[53]

In June 2022, Google Maps added a layer displaying air quality for certain countries.[54]

In September 2022, Google removed the COVID-19 Layer from Google Maps due to lack of usage of the feature.[55]

Google Maps provides a route planner,[56] allowing users to find available directions through driving, public transportation, walking, or biking.[57] Google has partnered globally with over 800 public transportation providers to adopt GTFS (General Transit Feed Specification), making the data available to third parties.[58][59] The app can indicate users' transit route, thanks to an October 2019 update. The incognito mode, eyes-free walking navigation features were released earlier.[60] A July 2020 update provided bike share routes.[61]

In February 2024, Google Maps started rolling out glanceable directions for its Android and iOS apps. The feature allows users to track their journey from their device's lock screen.[62][63]

In 2007, Google began offering traffic data as a colored overlay on top of roads and motorways to represent the speed of vehicles on particular roads. Crowdsourcing is used to obtain the GPS-determined locations of a large number of cellphone users, from which live traffic maps are produced.[64][65][66]

Google has stated that the speed and location information it collects to calculate traffic conditions is anonymous.[67] Options available in each phone's settings allow users not to share information about their location with Google Maps.[68] Google stated, "Once you disable or opt out of My Location, Maps will not continue to send radio information back to Google servers to determine your handset's approximate location".[69][failed verification]

On May 25, 2007, Google released Google Street View, a feature of Google Maps providing 360° panoramic street-level views of various locations. On the date of release, the feature only included five cities in the U.S. It has since expanded to thousands of locations around the world. In July 2009, Google began mapping college campuses and surrounding paths and trails.

Street View garnered much controversy after its release because of privacy concerns about the uncensored nature of the panoramic photographs, although the views are only taken on public streets.[70][71] Since then, Google has blurred faces and license plates through automated facial recognition.[72][73][74]

In late 2014, Google launched Google Underwater Street View, including 2,300 kilometres (1,400 mi) of the Australian Great Barrier Reef in 3D. The images are taken by special cameras which turn 360 degrees and take shots every 3 seconds.[75]

In 2017, in both Google Maps and Google Earth, Street View navigation of the International Space Station interior spaces became available.

Google Maps has incorporated[when?] 3D models of hundreds of cities in over 40 countries from Google Earth into its satellite view. The models were developed using aerial photogrammetry techniques.[76][77]

At the I/O 2022 event, Google announced Immersive View, a feature of Google Maps which would involve composite 3D images generated from Street View and aerial images of locations using AI, complete with synchronous information. It was to be initially in five cities worldwide, with plans to add it to other cities later on.[78] The feature was previewed in September 2022 with 250 photorealistic aerial 3D images of landmarks,[79] and was full launched in February 2023.[80] An expansion of Immersive View to routes was announced at Google I/O 2023,[81] and was launched in October 2023 for 15 cities globally.[82]

The feature uses predictive modelling and neural radiance fields to scan Street View and aerial images to generate composite 3D imagery of locations, including both exteriors and interiors, and routes, including driving, walking or cycling, as well as generate synchronous information and forecasts up to a month ahead from historical and environmental data about both such as weather, traffic and busyness.

Immersive View has been available in the following locations:[citation needed]

| Country | Locations |

|---|---|

| Buenos Aires | |

| Melbourne, Sydney | |

| Vienna | |

| Brussels | |

| Brasília, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo | |

| Calgary, Edmonton, Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto, Vancouver | |

| Santiago | |

| Prague | |

| Nice, Paris | |

| Berlin, Cologne, Frankfurt, Munich | |

| Athens | |

| Hong Kong | |

| Budapest | |

| Florence, Milan, Rome, Venice | |

| Kyoto, Nagoya, Osaka, Tokyo | |

| Guadalajara, Mexico City | |

| Amsterdam | |

| Oslo | |

| Warsaw | |

| Lisbon, Porto | |

| Bucharest | |

| Singapore | |

| Cape Town, Johannesburg | |

| Barcelona, Madrid | |

| Stockholm | |

| Zurich | |

| Taichung, Taipei | |

| Edinburgh, London | |

| Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Detroit, Houston, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Miami, New York City, Philadelphia, San Diego, San Francisco, Seattle | |

| Vatican City |

Google added icons of city attractions, in a similar style to Apple Maps, on October 3, 2019. In the first stage, such icons were added to 9 cities.[83]

In December 2009, Google introduced a new view consisting of 45° angle aerial imagery, offering a "bird's-eye view" of cities. The first cities available were San Jose and San Diego. This feature was initially available only to developers via the Google Maps API.[84] In February 2010, it was introduced as an experimental feature in Google Maps Labs.[85] In July 2010, 45° imagery was made available in Google Maps in select cities in South Africa, the United States, Germany and Italy.[86]

In February 2024, Google Maps incorporated a small weather icon on the top left corner of the Android and iOS mobile apps, giving access to weather and air quality index details.[87]

Previously called Search with Live View, Lens In Maps identifies shops, restaurants, transit stations and other street features with a phone's camera and places relevant information and a category pin on top, like closing/opening times, current busyness, pricing and reviews using AI and augmented reality. The feature, if available on the device, can be accessed through tapping the Lens icon in the search bar. It was expanded to 50 new cities in October 2023 in its biggest expansion yet, after initially being released in late 2022 in Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, London, and Paris.[88][89] Lens in Maps shares features with Live View, which also displays information relating to street features while guiding a user to a selected destination with virtual arrows, signs and guidance.[90]

Google collates business listings from multiple on-line and off-line sources. To reduce duplication in the index, Google's algorithm combines listings automatically based on address, phone number, or geocode,[91] but sometimes information for separate businesses will be inadvertently merged with each other, resulting in listings inaccurately incorporating elements from multiple businesses.[92] Google allows business owners to create and verify their own business data through Google Business Profile (GBP), formerly Google My Business (GMB).[93] Owners are encouraged to provide Google with business information including address, phone number, business category, and photos.[94] Google has staff in India who check and correct listings remotely as well as support businesses with issues.[95] Google also has teams on the ground in most countries that validate physical addresses in person.[96] In May 2024, Google announced it would discontinue the chat feature in Google Business Profile. Starting July 15, 2024, new chat conversations would be disabled, and by July 31, 2024, all chat functionalities would end.[97]

Google Maps can be manipulated by businesses that are not physically located in the area in which they record a listing. There are cases of people abusing Google Maps to overtake their competition by placing unverified listings on online directory sites, knowing the information will roll across to Google (duplicate sites). The people who update these listings do not use a registered business name. They place keywords and location details on their Google Maps business title, which can overtake credible business listings. In Australia in particular, genuine companies and businesses are noticing a trend of fake business listings in a variety of industries.[98]

Genuine business owners can also optimize their business listings to gain greater visibility in Google Maps, through a type of search engine marketing called local search engine optimization.[99]